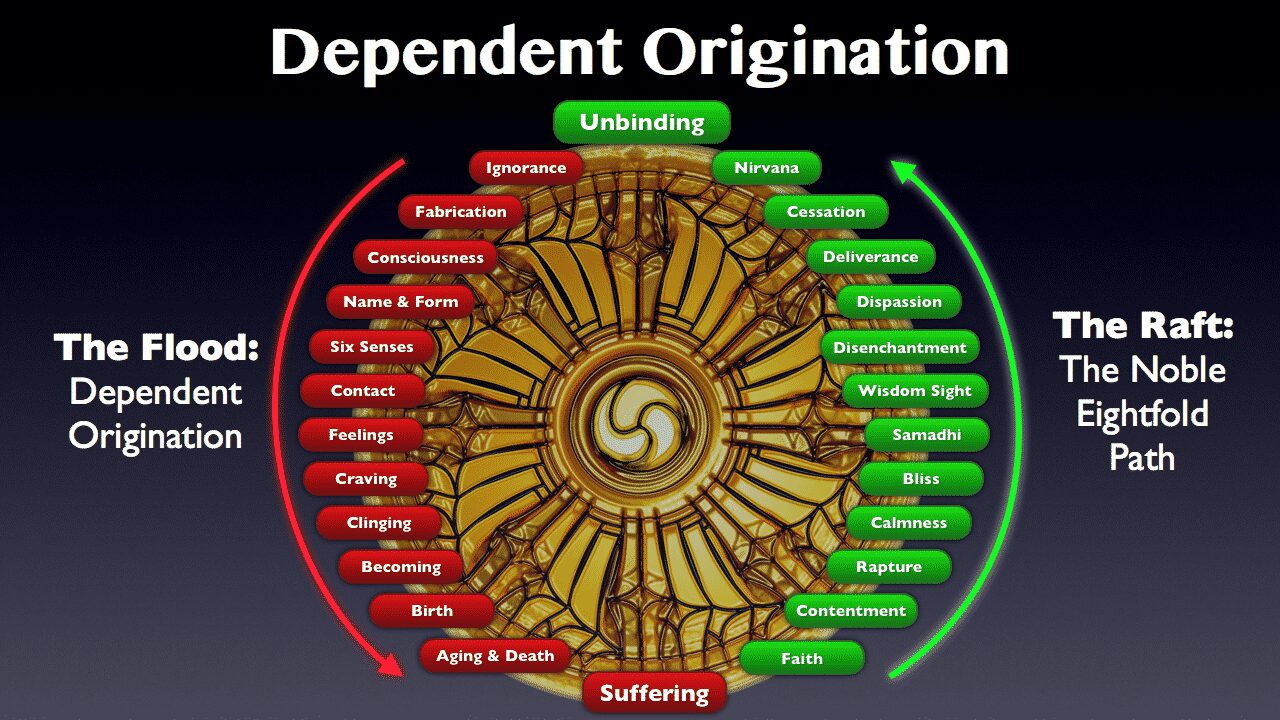

The principle of dependent origination— paṭicca-samuppāda — is a defining characteristic of Buddhist philosophy. Paṭicca-samuppāda explains the core statement of the Buddha, that the causes of sorrow and the causes of joy lie within our own hearts and minds, and within our own understanding or its absence. This is a very practical teaching.

Paṭicca-samuppāda is translated as dependent origination, or codependent arising, or causal interdependence. It is considered by the Buddha to be a universal law governing human consciousness, perception and action. The term may also refer to the Twelve Nidānas, the twelvefold chain that describes the chain of endless rebirth in Saṃsāra. In the Mahayana tradition, paṭicca-samuppāda is used to refer to the general principle of interdependent causation, whereas in the Theravada tradition, paṭicca-samuppāda is used to refer to the Twelve Nidanas.

Dependent origination is the central principle of the Buddha’s teaching, constituting both the objective content of its liberating insight and the germinative source for its vast network of doctrines and disciplines. The Pali texts present dependent origination in a double form. It appears both as an abstract statement of universal law and as the particular application of that law to the specific problem which is the doctrine’s focal concern, namely, the problem of suffering. In its abstract form, the principle of dependent arising is equivalent to the law of the conditioned genesis of phenomena. It expresses the invariable concomitance between the arising and ceasing of any given phenomenon and the functional efficacy of its originative conditions.

Paṭicca-samuppāda describes the way in which our personal world is constructed and created, moment to moment. According to the Buddha, human experience is patterned in a way that is clearly discernible to us when we investigate this law. So paṭicca-samuppāda describes not only the way in which our personal world forms and changes and fades away; it also describes the ways in which suffering, struggle and confusion are created and constructed.

Paṭicca-samuppāda is describing a natural law, the interdependent nature of all things, the contingent nature of all things. So what is essentially being described in paṭicca-samuppāda is the teaching of contingency, the complex of conditions giving rise to a matrix of experience. This law shows that there is nothing that is separate, nothing that has independent self-existence.

Paṭicca-samuppāda is not only describing the way things are, but the way they can be. In other words, its dynamic nature is the key to the possibility of liberation.

The Buddha did not talk about a causal structure in which one thing simply causes another; that is just a linear way of seeing. He said that when certain conditions are present, a certain event will occur. Certain conditions come together, have a certain fruition in a particular event, which in turn changes into other events. Change those conditions and a different event will occur.

On a coarse level, dependent origination refers simply to something’s dependence on causes and conditions, and explains the origination of everything in terms of cause and effect. According to Buddhists, such changes do not happen due to God’s wish; instead, they happen as a result of our implementation of proper causes.

There are three levels of understanding of paṭicca-samuppāda, beginning with the dependence of things and events on their causes and conditions.

Second, is the understanding of dependent origination in respect to the relationship between parts and the whole.

Ultimately is the concept of dependent designation. This third one means arising in dependence upon term and concept – also called existing by being mere name. This means that something doesn’t exist as a certain object until it is labeled by that name.

The first of these three dependent relationships is limited to effects resulting from their causes. The relationship is valid in only one temporal direction, as the flow of time from past to future prohibits a cause from depending on its effect in the sense of resulting from it. Altough something can only be identified as an effect in respect to its cause, the reverse is also true: A cause can only be identified as a cause in respect to its effect. Its causal identity is dependent on its subsequent effect. In this sense, the dependent relationship operates in both temporal directions.

Though a cause cannot be the effect of itself, nevertheless it is necessarily the effect of a cause other than itself. The sprout is the effect of its causal seed while also being the cause of the future tree. This demonstrates that no cause is an absolute cause, in and of itself. Causes are only causes in dependence upon their effects, while also being effects in dependence upon their own causes. Anything may, therefore, be called a cause in dependence upon its having an effect, and an effect in dependence upon its having been caused. Nothing has the inherent quality of being either a cause or an effect, as this would prohibit the cause being anything but a cause, or the effect being anything but an effect.

This understanding allows us to grasp its subtler interpretations regarding the emptiness. The Buddhist term emptiness (Skt. śūnyatā) refers specifically to the idea that everything is dependently originated, including the causes and conditions themselves, and even the principle of causality itself.

Conversely, our understanding of emptiness as mere designation enables us to better understand the dependent relationship between things and their parts, which will, in turn, deepen our understanding of the mechanics of cause and effect.

„As we develop our insight into emptiness, we must also work to purify our motives for pursuing this wisdom aspect of the path to enlightenment. Wisdom alone will not lead us to the ultimate state of Buddhahood. We must develop the method aspect of the path by which we can serve the sentient beings and lead them toward happiness and freedom from all levels of suffering.” Dalai Lama

This is how the Buddha often presented paṭicca-samuppāda. He said “When there is this, that is; with the arising of this, that arises; when this is not, neither is that. With the cessation of this, that ceases.” That is the basic formula.

photo credit: thabarwa