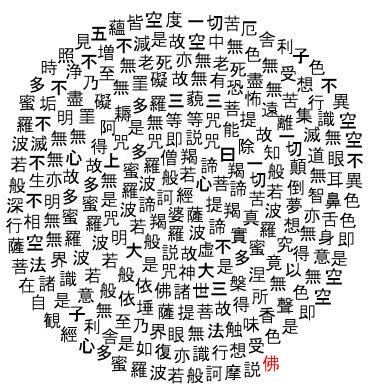

KAN JI ZAI BO SA GYO- JIN HAN-NYA HA RA MI TA JI

Avalokitesvara Bodhisattva, while meditating deeply in the Prajñaparamita,SHO- KEN GO ON KAI KU- DO IS-SAI KU YAKU.

clearly perceived that all five skandhas are equally empty, overcoming all suffering.SHA RI SHI SHIKI FU I KU- KU- FU I SHIKI

“Listen, Shariputra, form does not differ from emptiness, nor emptiness from form.SHIKI SOKU ZE KU- KU- SOKU ZE SHIKI

Form is emptiness, emptiness is form.JU SO- GYO- SHIKI YAKU BU NYO ZE

The same thing is true with feelings, perception, mental functioning, and consciousness.SHA RI SHI ZE SHO HO- KU- SO- FU SHO- FU METSU

“Shariputra, all things are marked with emptiness; they are neither produced nor destroyed;FU KU FU JO- FU ZO- FU GEN

neither stained nor pure, neither increasing nor decreasing.ZE KO KU- CHU- MU SHIKI MU JU SO- GYO- SHIKI

“Therefore, in emptiness there is neither form, nor feeling, nor perception, nor mental functioning, nor consciousness;MU GEN-NI BI ZES-SHIN I

no eye, no ear, no nose, no tongue, no body, no mind;MU SHIKI SHO- KO- MI SOKU HO-

no form, no sound, no smell, no taste, no touchable, no object of mind;MU GEN KAI NAI SHI MU I SHIKI KAI

no realm of eyes, and so forth until no realm of mind consciousness.MU MU MYO- YAKU MU MU MYO- JIN

“No ignorance and also no extinction of ignorance,NAI SHI MU RO- SHI YAKU MU RO- SHI JIN

no old age and death, and so forth until no extinction of old age and death.MU KU SHU METSU DO-Y

“No suffering, no origination of suffering, no extinction of suffering, and no path.MU CHI YAKU MU TOKU I MU SHO TOK’KO

No wisdom and also no attainment. With nothing to attain,BO DAI SAT-TA E HAN-NYA HA RA MI TA KO

the bodhisattva, relies on Prajñaparamita,SHIM-MU KEI GE MU KEI GE KO MU U KU FU

has no hindrance in his mind. Without any hindrance in his mind, there is no fear.ON RI IS-SAI TEN DO- MU SO- KU GYO- NE HAN

Liberating himself forever from illusion and dream, realizing perfect Nirvana.SAN ZE SHO BUTSU E HAN-NYA HA RA MI TA KO

“All Buddhas in the past, present, and future, rely on Prajñaparamita,TOKU A NOKU TA RA SAM-MYAKU SAM-BO DAI

attain Anuttara Samyak Sambodhi.KO CHI HAN-NYA HA RA MI TA

“Therefore, one should know that PrajñaparamitaZE DAI JIN SHU ZE DAI MYO- SHU

is the great sacred mantra, is the great vivid mantra,ZE MU JO- SHU ZE MU TO- TO- SHU

is the supreme mantra, is the unequaled mantra,NO- JO IS-SAI KU SHIN JITSU FU KO

that can liberate all suffering truly and indeed.KO SETSU HAN-NYA HA RA MI TA SHU SOKU SETSU SHU WATSU

A mantra of Prajñaparamita should therefore be proclaimed:GYA TEI GYA TEI HA RA GYA TEI HARA SO- GYA TEI BO JI SOWA KA

Gate, gate, paragate, parasamgate, bodhi svaha.HAN-NYA SHIN GYO

Sutra on the heart of the perfection of wisdom

The title of this sutra is The Essence of Wisdom, often known as the Heart Sutra. This sutra contains the heart (or essence) of the Prajnaparamita Sutras, the most important teachings of the Buddha. Prajnaparamita means the Perfection of Wisdom, the Wisdom Gone Beyond or the Transcendental Wisdom.

Prajna means wisdom, the great transcendental wisdom, wisdom from understanding the truth, wisdom that can overcome birth-and-death, all suffering, and enlighten all beings.

Paramita means “going beyond,” or perfecting. It is the perfection, the practice that can bring one to liberation. Literally means “to the other shore.” To become a Buddha, the bodhisattva practices the six paramitas: the perfection of charity (dana), moral conduct (sila), tolerance (ksanti), diligence (virya), meditation (dhyana), and, most important of all, wisdom (prajna).

Hrdaya means heart. And the Chinese characters for Heart Sutra can be translated as “mind road.” So this sutra is the “great path for the perfection of wisdom.”

*

Among the Prajnaparamita Sutras are the extensive, medium and concise Mother Sutras.

The great or extensive one is the Perfection of Wisdom in 100,000 verses; The Perfection of Wisdom collection was originally written in Buddhist Sanskrit, which is slightly different from classical Sanskrit.

The medium one is that in 20,000 verses and the concise one is in 8,000 verses.

The Essence of Wisdom sutra is called like this because it contains the essence of all of the Wisdom Sutras. There is a number of Heart Sutras, both long and short. The long version of the Heart Sutra has been translated and published in many versions. The short one is the most common Buddhist Sutra being used – and highly revered – by all the Buddhist practitioners.

The Heart Sutra is a teaching given by the Bodhisattva Avalokitesvara, the Buddha of Compassion, to the monk Shariputra. It is chanted regularly by followers of Buddhism at meetings and meditation practice. Although The Heart Sutra is very brief, it contains key concepts of Buddhist Philosophy.

These include the skandhas, the four noble truths, the cycle of interdependence and the central concept of Mahayana Buddhism, Emptiness.

Sutra: a Buddhist scripture, spoken by the Buddha or certified (to be true) by the Buddha. A striking feature of this sutra is the fact that its teaching is not actually delivered by the Buddha, which places it in a relatively small class of those ‘’sutras not directly spoken by the Buddha’’. In some Chinese versions of the text, the Buddha confirms and praises the words of Avalokitesvara.

So, both question and the answer arise through the blessing of the Buddha and are called the holy word of the Buddha. (There are different types of word or teaching of the Buddha, and one is called the holy word when comes through the blessing of the Buddha). Although spoken by Shariputra and Avalokiteshvara, with the question coming from Shariputra, and Avalokiteshvara giving the answer, it is still referred to as the Buddha’s word, because at the very end of the sutra it is said, ‘’At that time, the Lord arose from his concentration, and said to the noble Avalokiteshvara,

“Well said, well said, that is just how it is my son, just how it is. The profound perfection of wisdom should be practiced exactly as you have explained it, then the Tathagata will be truly delighted.’’

Avalokitesvara is an enlightened being, a Bodhisattva, who has forgone his own entry into Nirvana so that he can help others. In the Heart Sutra, he has realized emptiness through the practice of Prajna-paramita (infinite wisdom) and is preaching to the monk Shariputra.

Sariputra: A senior disciple of the Buddha, known for his wisdom.

Emptiness is how the Sanskrit noun Sunyata is translated into English. The adjective form is Sunya, Empty. (The Japanese Buddhists use the term ku and the Chinese Buddhists use the term mu). Emptiness is not nothingness. It is the other side of interdependence (pratityasamutpada). All things are inter-related and an object is not independent of the rest. Its existence has no self-being (svabhava).

The five skandhas (aggregates) are form, feelings, perceptions, impulses, consciousness.

The form is the solid object, the colour or the sound that is interdependent with the other skandhas. For example a hot stove.

Feeling is the act of the sense organ contacting the object. The skin feels the eye sees, the ears hear. For example, when the skin comes in contact with a hot stove.

Perception is the first sensational awareness of the object. For example, the skin becomes hot when it touches the stove.

In Buddhism, perception is realized by the six senses:

seeing, hearing, smelling, tasting, touching, mind. We usually think of the mind as separate from the other senses, but when we are conscious of an object, or we dream or think of something that is not in front of us, our mind acts as a sense organ. Each sense has three parts, the organ of sense, its object, and its realm of consciousness (datu). For example, the eye sees the colour green, which gives rise to the consciousness of green. Yet, each of these parts is empty, since they are interdependent and cannot be separated. Three parts and six senses give us the eighteen elements of experience.

Impulse is the unconscious reaction to the object. We place our hand on a hot stove and our impulse is to pull it away before we even think. It is the action.

Consciousness is mental awareness of the object. One feels the heat on the hand and thinks, “Ouch!”

Each of the above skandhas is empty since it cannot exist on its own and it is dependent on the four other skandhas. Like a set of blocks forming a house, the entire structure is dependent on its pieces.

The term dharmas is different from the Dharma, the Way or the Teaching. Dharmas are factors of existence. The five skandhas are dharmas. The Hinayana schools consider that the dharmas have qualities, such as arising or disappearing, increasing or decreasing, but the Mahayanists realized that dharmas are empty, without qualities, so the five skandhas are empty (since they are interdependent dharmas, and have no self-qualities).

– The Prajnaparamita Sutra explicitly reveals the stages of profound emptiness. Implicitly, it explains the grounds and paths, the various realisations (produced or arising sequentially) in the mind of the practitioner who is gradually progressing through the path.

– What the Heart Sutra (like all Prajnaparamita Sutras) does, is to cut through, deconstruct, and demolish all our usual conceptual frameworks, all our rigid ideas, all our belief systems, all our reference points, including any with regard to our spiritual path. It does so on a very fundamental level, not just in terms of thinking and concepts, but also in terms of our perception, how we see the world, how we hear, how we smell, taste, touch, how we regard and emotionally react to ourselves and others, and so on.

– Another way to look at the Heart Sutra is that it represents a very condensed contemplation manual. It is not just something to be read or recited, but the intention is to contemplate its meaning in as detailed a way as possible.

– Besides being a meditation manual, we could also say that the Heart Sutra is like a big koan. But it is not just one koan, it is like those Russian dolls: there is one big doll on the outside and then there is a smaller one inside that first one, and there are much smaller ones in each following one. Likewise, all the words “no” in the big koan of the sutra are little koans. Every little phrase with a “no” is a different koan in terms of what the “no” relates to, such as “no eye,” “no ear,” and so on. In other words, all those different “no” phrases give us different angles or facets of the main theme of the sutra, which is emptiness. Emptiness means that things do not exist as they seem, but are like illusions and like dreams. They do not have a nature of their own.

Each one of those phrases makes us look at that very same message. The message or the looking are not really different, but we look at it in relation to different things. What does it mean that the eye is empty? What does it mean that visible form is empty? What does it mean that even wisdom, buddhahood, and nirvana are empty?

– This scripture has always been held in the greatest veneration in Mahayana countries. The Prajnaparamita-Sutra is regarded as the holy mother that feeds the bodhisattva with the amrita (nectar) of prajna (transcendental wisdom) and guides a bodhisattva to paramita (the other shore). It is the “utmost great perfection” which gives full enlightenment to the bodhisattva after he has successfully completed the other five paramitas: dana (charity), sila (morality), ksanti (patience, forbearance), virya (energy), and dhyana (concentration).

“There is no attainment and no non-attainment.”

photo credit: Maka