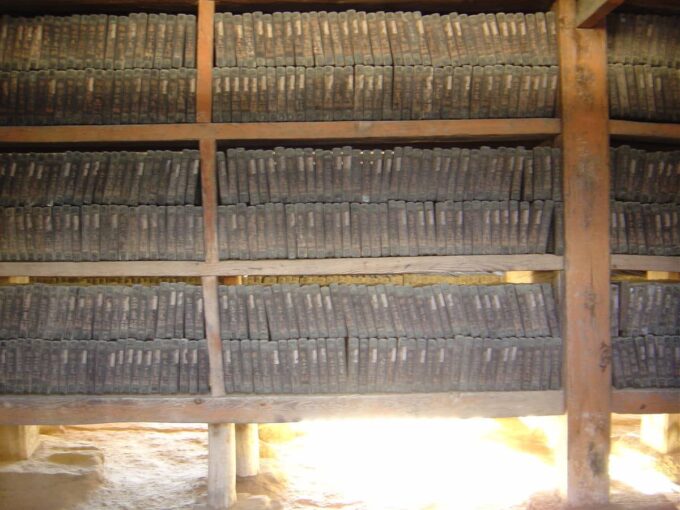

The Tripitaka is a collection of holy writings organized into three collections or baskets to include the rules for monastics (The Vinaya), the actual teachings of Buddha Shakyamuni (The Suttas or Sutras), and the commentaries or abhidharma. Tripitaka – “The Three Baskets”, was compiled at the council at Pataliputra (3rd century BCE) 300 years after the Buddha’s mahaparinibbana (attainment of final nibbana upon death), where both the canonical and philosophical doctrines of early Buddhism were codified. Several of these collections are still existing in the world today, including the Theravada Canon recorded in Pali, the Chinese Canon, and the Tibetan Canon.

Vinaya Pitaka is a collection of texts concerning the rules of conduct governing the daily affairs within the Sangha — the community of bhikkhus (ordained monks) and bhikkhunis (ordained nuns). Far more than merely a list of rules, the Vinaya Pitaka also includes the stories behind the origin of each rule, providing a detailed account of the Buddha’s solution to the question of how to maintain communal harmony within a large and diverse spiritual community.

The Vinaya was orally passed down from the Buddha to his disciples. Eventually, numerous different Vinayas arose in Buddhism, based upon geographical or cultural differences and the different schools of Buddhism that developed. Three of these are still in use: Theravadin (Theravada), Mulasarvastivadin (the schools of Tibetan Buddhism) and Dharmaguptakin (East Asian Buddhism). The Vinayas are the same in substance and have only minor differences.

This Pitaka consists of the five following books:

- Parajika Pali (Major Offences)

- Pacittiya Pali (Minor Offences)

- Mahavagga Pali (Greater Section)

- Cullavagga Pali (Smaller Section)

- Parivara Pali (Epitome of the Vinaya)

There are several moral codes for monastics, and they can be found in the following works:

- Ovada Patimokkha: Early teaching of Buddha on basic rules for the Sangha.

- Bhikkhuni Patimokkha–Theravada: 311 rules for nuns from the Theravadan School.

- Bhikkhuni Patimokkha–Mahasanghika: 290 rules for nuns from the Mahasanghika School.

- Bhikkhuni Patimokkha–Mahisasaka: 380 rules for nuns from the Mahisasaka School.

- Bhikkhuni Patimokkha–Sarvastivada: 354 rules for nuns from the Sarvastivada School.

- Bhikkhuni Patimokkha–Dharmagupta: 348 rules for nuns from the Dharmagupta School.

- Bhikkhuni Patimokkha–Mula-Sarvastivada: 346 rules for nuns from the Mula-Sarvastivada School.

- Bhikkhuni Patimokkha: 311 rules for nuns.

- Bhikkhu Patimokkha: 227 rules for monks.

The Sutta Pitaka contains more than 10,000 suttas (teachings) attributed to the Buddha or his close companions. “Sutta” is the Pali word for “Sutra.” Sutra is the Sanskrit term used to classify the Mahayana teachings of the Buddha. Buddha taught 84,000 dharmas for the 84,00 afflictions. He taught so that sentient beings of varying capacities and backgrounds could understand the Dharma. Just as different medicine may be prescribed for different illnesses or at different stages in any given illness, the Buddha conveyed his great wisdom in many ways. They are excellent for those just beginning the path and seeking a solid foundation in the Buddha’s teachings. Most of these were composed in India in Sanskrit and transmitted to China, Korea, Japan, Tibet, and Mongolia where they were translated into the local languages.

There are five nikayas (collections) of suttas:

- Digha Nikaya (dīghanikāya), the “long” discourses. This includes The Greater Discourse on the Foundations of Mindfulness, The Fruits of the Contemplative Life, and The Buddha’s Last Days. There are 34 long suttas in this nikaya.

- Majjhima Nikaya, the “middle-length” discourses. This includes Shorter Exposition of Kamma, Mindfulness of Breathing, and Mindfulness of the Body. There are 152 medium-length suttas in this nikaya.

- Samyutta Nikaya (saṃyutta-), the “connected” discourses. There are, according to one reckoning, 2,889, but according to the commentary 7,762, shorter suttas in this Nikaya.

- Anguttara Nikaya (aṅguttara-), the “numerical” discourses. These teachings are arranged numerically. It includes, according to the commentary’s reckoning, 9,565 short suttas grouped by the number. According to some sources, “there is considerable disparity between the Pāli and the Sarvāstivādin versions, with more than two-thirds of the sūtras found in one but not the other compilation, which suggests that much of this portion of the Sūtra Piṭaka was not formed until a fairly late date.”

- Khuddaka Nikaya, the “minor collection”. This is a heterogeneous mix of sermons, doctrines, and poetry attributed to the Buddha and his disciples. The contents vary somewhat between editions.

The Abhidhamma Pitaka is a detailed scholastic reworking of material appearing in the Suttas, according to schematic classifications. It does not contain systematic philosophical treatises, but summaries or enumerated lists. In its most characteristic parts it is a system of classifications, analytical enumerations and definitions, with no discursive treatment of the subject matter.

The Abhidhamma Pitaka contains the profound moral psychology and philosophy of the Buddha’s teaching, in contrast to the simpler discourses in the Sutta Pitaka. Some scholars assert that the Abhidhamma is not the teaching of the Buddha, but it grew out of the commentaries on the basic teachings of the Buddha. These commentaries are said to be the work of great scholar monks. Tradition, however, attributes the nucleus of the Abhidhamma to the Buddha Himself.

In particular, its two important books, the Dhammasangani and the Patthana, have the appearance of huge collections of systematically arranged tabulations, accompanied by definitions of the terms used in the tables. Because of its complexity and profound teaching, Abhidhamma was, and is, highly esteemed and even venerated in the countries of Theravada Buddhism.

The seven books of the Abhidhamma Pitaka offer an extraordinarily detailed analysis of the basic natural principles that govern the mental and physical processes. Whereas the Sutta and Vinaya Pitakas lay out the practical aspects of the Buddhist path to Awakening, the Abhidhamma Pitaka provides a theoretical framework to explain the causal underpinnings of that very path.

The term Tripiṭaka had tended to become synonymous with Buddhist scriptures, and thus continued to be used for the Chinese and Tibetan collections, although their general divisions do not match a strict division into three piṭakas. In the Chinese tradition, the texts are classified in a variety of ways, most of which have in fact four or even more piṭakas or other divisions.

photo credit: DavidGalarza