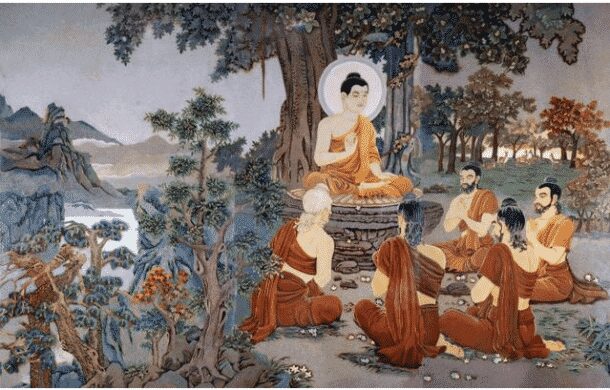

The Buddha was a totally realized being who manifested a human birth in India in the fifth century B.C.E. in order to be able to teach other human beings by means of his words and by the example of his life. Suffering is something very concrete, which everyone knows and wants to avoid if possible, and the Buddha, therefore, began his teaching by talking about it in his famous formulation of the Four Noble Truths.

The first truth draws our attention to the fact that we suffer, pointing out the existence of the basic dissatisfaction inherent in our condition; the second truth explains the cause of dissatisfaction, which is the dualistic state and the unquenchable thirst (or desire) inherent in it: the subject reifies its objects and tries to grasp them by any means, and this thirst (or desire) in turn affirms and sustains the illusory existence of the subject as an entity separate from the integrated wholeness of the universe. The third truth teaches that suffering will cease if dualism is overcome and reintegration achieved so that we no longer feel separate from the unity with all the things in the universe. Finally, the fourth truth explains that there is a Path that leads to the cessation of suffering, which is the one described by the rest of the Buddhist teachings.

All the various Buddhist traditions agree that this basic problem of suffering exists, but they have different methods of dealing with it in order to bring the individual back to the experience of primordial unity.

The Hinayana tradition of Buddhism follows the Path of Renunciation that was taught by the Buddha in his human form and later written down in what are known as the Sutras. În Hinayana, the ego is regarded as a poisonous tree, and the method applied is like digging up the roots of the tree, one by one. One has to overcome all the habits and tendencies that are considered negative and are hindrances to liberation. There are many rules of conduct, governed by vows that regulate all one’s actions. The ideal is that of the monk or nun – who takes the maximum number of vows. If one’s ordinary way of being – whether it is a monk or a lay practitioner – is considered impure and to be renounced, that person has to recreate him/herself as a pure individual – going through the development of various states of meditation – becoming the one who has gone beyond the causes of suffering, the ‘Arhat,’ the one who returns no more to the cycles of births and deaths of the conditioned existence.

From the point of view of the Mahayana, to seek only one’s own salvation in this way, and to go beyond suffering whilst others continue to suffer, is less than ideal. In the Mahayana it is considered that one should work for a greater good, putting the wish for the realization of all others before one’s own realization, and indeed continually returning to the cycles of suffering in order to help others to get beyond it. One who practices in this way is called a Bodhisattva.

Hinayana, or Lesser Vehicle, and Mahayana, or Greater Vehicle, are both parts of the Path of Renunciation, but their characteristic approaches are different. Since to cut through the roots of a tree one by one takes a long time, the Mahayana works more to cut the main root, so that the other roots may wither by themselves. The way to cut the main root is considered to be to discover the essential voidness, both of the subject and of all objects and to develop supreme compassion. Whereas the Mahayana posits the voidness of both the subject and its objects and tells us to work toward realizing (or discovering) both, in the Hinayana only the voidness of the ego is posited and must be discovered. In the Mahayana, the intention behind one’s actions is considered as important as one’s actions themselves, which is a different approach from that of governing all one’s actions with vows as one does in the Hinayana.

Both the levels of the Path of Renunciation, Hinayana and Mahayana, are said to work at the level of Body.

Source: Namkhai Norbu, Teachings

Photo credit: sobrebudismo