The Laṅkāvatāra Sūtra is one of the most important sutras (sacred texts) of Mahayana Buddhism. According to tradition, these are the actual words of the Buddha as he entered Sri Lanka (formerly called Ceylon). The sutra is set in Laṅkā, the island fortress capital of Rāvaṇa, the king of rākṣasas. The title of this text roughly translates as, “Scripture of the Descent into Laṅkā” or “Sutra of the Appearance of the Good Doctrine in Lanka”), in full, Saddharma-lankavatara-sutra. The sutra recounts a teaching primarily between the Buddha and a bodhisattva named Mahāmati (“Great Wisdom”).

Nothing is known as to its author, the time of its composition, or as to its original form. There is a myth that it originally consisted of 100,000 verses, and the second chapter of the present text has a footnote which reads: “Here ends the second chapter of the Collection of all the Dharmas, taken from the Lankavatara of 36,000 verses.”

Apparently, it was originally a collection of verses covering all the main teachings of Mahayana Buddhism. This vast collection of verses became a source from which the Masters selected texts for their discourses. As the verses were very epigrammatic, obscure and disconnected, in the course of time the discourses were remembered and the verses largely forgotten, until in the present text there are remaining only 884 verses.

The earliest date connected with it is the date of the first Chinese translation made by Dharmaraksha about A.D. 420 and which was lost before 700. Three other Chinese translations have been made: one by Gunabhadra in 443; one by Bodhiruci in 513; and one by Shikshananda about 700. There is also one Tibetan version. According to one scholar, “it is generally believed that the sutra was compiled during 350-400 CE,” although “many who have studied the sutra are of opinion that the introductory chapter and the last two chapters were added to the book at a later period.”

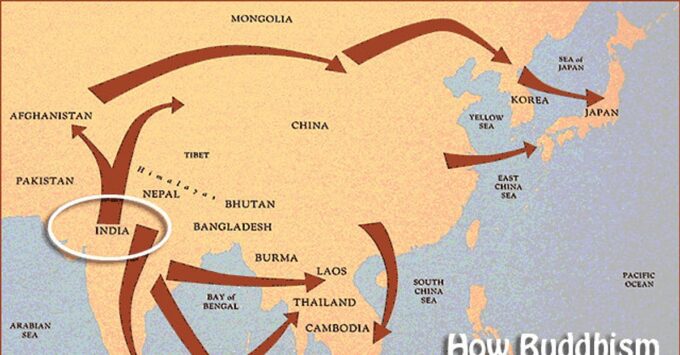

The Sutra has always been a favorite with the Ch’an Sect (Zen, in Japan) and has had a great deal to do with that sect’s origin and development. There is a tradition that when Bodhidharma handed over his begging-bowl and robe to his successor, Huike (Eka), that he also gave him his copy of the Lankavatara, saying, that he needed no other sutra. In the early days of the Ch’an Sect the Sutra was very much studied, but because of its difficulties and obscurities it gradually dropped out of common use and has been very much neglected. But during that time many of the great Masters have made it a subject of study, and many commentaries have been written upon it. Although other sutras have been more commonly read, none have been more influential in fixing the general doctrines of Mahayana Buddhism, and in bringing about the general adoption of Buddhism in China, Korea and Japan.

This sutra figured prominently in the development of Chinese, Tibetan and Japanese Buddhism. It is the cornerstone of Chinese Chan and its Japanese version, Zen, and was translated from Sanskrit into Japanese and English by Daisetz Teitaro Suzuki.

This sutra not only represents a comprehensive synthesis of both early and late religio-philosophical ideas crucial to the understanding of Buddhism in India, but it also provides an insight into the very early roots of the Japanese Zen Buddhism in the heart of the South Asian esotericism.

Laṅkāvatāra Sūtra is not written as a philosophical treatise is written, to establish a certain system of thought, but was written to elucidate the profoundest experience that comes to the human spirit. It everywhere deprecates dependence upon words and doctrines and urges upon all the wisdom of making a determined effort to attain this highest experience. Again and again, it repeats with variations the refrain: “Mahamati, you and all the Bodhisattva-Mahasattvas should avoid the erroneous reasonings of the philosophers and seek this self-realisation of Noble Wisdom.”

For this reason, the Laṅkāvatāra Sūtra is to be classed with the intuitional scriptures of the Orient, rather than with the philosophical literature of the Occident. In China it combined easily with the accepted belief of the Chinese in Laotsu’s conception of the Tao and its ethical idealism to make the Buddhism of China and Japan eminently austere and practical, rather than philosophical and emotional.

The Laṅkāvatāra Sūtra draws upon the concepts and doctrines of Yogācāra and Tathāgatagarbha. The most important doctrine issuing from the Laṅkāvatāra Sūtra is that of the primacy of consciousness (Skt. vijñāna) often called simply “Mind Only” – the teaching of consciousness as the only reality. The sūtra asserts that all the objects of the world, and the names and forms of experience, are merely manifestations of the mind. The Laṅkāvatāra Sūtra describes the various tiers of consciousness in the individual, culminating in the “storehouse consciousness” (Skt. Ālayavijñāna), which is the base of the individual’s deepest awareness and his tie to the cosmic.

The Laṅkāvatāra Sūtra also suggests another important Mahayana doctrine, developed in later Buddhism, and that is the three bodies of Buddhahood, in effect the three levels of enlightened reality:

– transcendental dimension (Sanskrit dharmakaya) – the ultimate level of enlightenment, which is beyond names and forms

– celestial dimension, (Sanskrit sambhogakaya) – expression of the symbolic and archetypal dimension of Buddhahood, to which only the spiritually developed have access

– terrestrial or transformational dimension, (Sanskrit nirmanakaya) – The dimension of Buddhahood to which the unenlightened have access, and where the phenomena of the world exist.

Laṅkāvatāra Sūtra teaches that the world is an illusory reflection of ultimate, undifferentiated mind and that this truth suddenly becomes an inner realization in concentrated meditation.

photo credit: idpuk