There are many different ways of understanding mindfulness: as a personality trait, as a meditative state and practice from the Buddhist traditions, as a cognitive faculty, or a philosophical way of being-in-the-world. Mindfulness has roots in Buddhist philosophy and religion – much of what we hear about mindfulness comes from secularized versions of the ancient Buddhist practice – and is considered an important aspect of practice for the path to enlightenment.

Wikipedia says:

„Enlightenment (bodhi) is a state of being in which greed, hatred and delusion (Pali:moha) have been overcome, abandoned and are absent from the mind. Mindfulness, which, among other things, is an attentive awareness of the reality of things (especially of the present moment) is an antidote to delusion and is considered as such a ‘power’ (Pali:bala). This faculty becomes a power in particular when it is coupled with clear comprehension of whatever is taking place.”

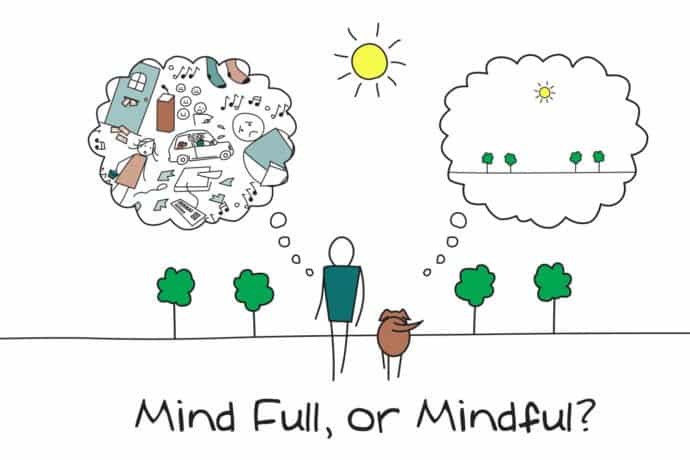

Mindfulness is a way of working with our attention focused on the present moment in a nonjudgmental way. It’s not about what we experience, but how we experience things, whether they are pleasant, unpleasant, or neutral.

Mindfulness is a state of active, open attention on what is happening in front of our eyes. When we are mindful, we observe our thoughts and feelings from a distance, without judging them in terms of good or bad. Instead of letting our life pass us by, mindfulness means living in the moment and awakening to the actual experience. Mindfulness is a way of bringing us back to experience life as it happens.

When we are mindful, we:

- Focus on the present moment

- Try not to think about anything that went on in the past, or that might be coming up in future

- Purposefully concentrate on what’s happening around us

- Try not to be judgemental about anything we notice, or label things as ‘good’ or ‘bad’

Being mindful, it:

- Helps clear our head, to be more aware of ourselves, our body and the environment

- Helps to slow down the thoughts, slows down the nervous system

- Helps us to concentrate, helps us to relax, helps to improve our sleep

- Can help us to cope with stress and pain

- Help us to manage depression and/or anxiety, to be less angry or moody

- Improve our memory, help us to learn or solve problems more easily

- Make us happier and more emotionally stable

- Improve our breathing, our heart rate, our circulation, our immunity system,

Mindfulness is something that everyone can develop, and it’s something that everyone can try. People can increase their mindfulness in everyday life, through activities like meditation and yoga, or even by simply paying more attention during regular activities like walking, driving or something as basic as brushing the teeth.

We can think of mindfulness as simply being fully in the moment (Dr. Jon Kabat-Zinn defines it as “paying attention on purpose, in the present moment, non-judgmentally—as if your life depended on it). Being mindful ‘one hundred percent’ doesn’t come easy, especially in a world full of distractions. It means actively listening and it means using all our senses in even mundane situations.

Mindfulness does not conflict with any beliefs or tradition, religious, cultural or scientific. It is simply a practical way to notice thoughts, physical sensations, sights, sounds, smells – anything we might not normally notice. The actual skills might be simple, but because it is so different to how our minds normally behave, it takes a lot of practice.

Being mindful helps us to train our attention. Our minds wander about 50% of the time, but every time we practise being mindful, we are exercising our attention “muscle” and becoming mentally fitter. We can take more control over our focus of attention, and choose what we focus on, rather than passively allowing our attention to be dominated by that which distresses us and takes us away from the present moment. Mindfulness might simply be described as choosing and learning to control our focus of attention, and being open, curious and flexible.

By becoming more aware of our thoughts, feelings, and body sensations, from moment to moment, we give ourselves the possibility of greater freedom and choice. The more we practice, the more we will notice the intruding thoughts. The only aim of mindful activity is to continually bring our attention back to the actual experience, noticing the sensations, coming from outside and from within us.

Over the last 30 years, mindfulness has become secularised and simplified to suit a Western context. In the 1970s the research findings about the ability of meditation to reduce unhealthy psychological symptoms triggered interest in mindfulness as a healthcare intervention. Jon Kabat-Zinn at the Medical Centre at the University of Massachusetts introduced the first eight week structured mindfulness skills training programme which gave considerable psychological, and some physical, relief, to patients experiencing intractable severe pain and distress from a wide range of chronic physical health conditions. This came to be known as MBSR (Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction). In 2002, Mark Williams, professor of clinical psychology at the Oxford Mindfulness Centre, and his colleagues from Cambridge and Toronto universities, devised Mindfulness-Based Cognitive Therapy for Depression, aimed at helping prevent the relapse of depression

Mindfulness is both a practice and a state of mind. For example, when we practice mindfulness meditation, we are sharpening our focus (usually by paying more attention to the breath) and training our brain to be more mindful long after we are done meditating.

Mindfulness has many synonyms. It is called awareness, attention, focus, presence, or vigilance. The opposite, then, is not just mindlessness, but also distractedness, inattention, and lack of engagement.

“Mindfulness is awareness that arises through paying attention, on purpose, in the present moment, non-judgementally,” says Kabat-Zinn. “It’s about knowing what is on your mind.”