Buddhism is one of the oldest religions of the world. Buddhism is practiced by a large number of people in many parts of the world, particularly in the South East Asian countries. Like any other religious tradition, Buddhism has undergone a number of different transformations that have led to the emergence of many different Buddhist schools. As Buddhism made progress and spread to different parts of the world, new thoughts and improvisations came to be attached to the existing beliefs and practices. This process led to the development and evolution of different schools or sects.

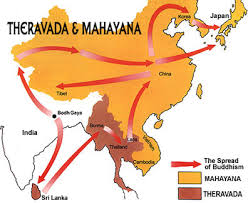

Surviving schools of Buddhism can be roughly grouped as Theravada, Mahayana and Vajrayana. Most of the Buddhist schools and sects encourage followers to adhere to certain practices and philosophies. Some of these philosophies and practices are common, whereas some unique to the particular school or sect.

Today, the four major Buddhist branches are Mahayana, Theravada, Vajrayana and Zen Buddhism. This classification is simply one of the many we find in the scholarly literature and by no means is it set in stone.

About a century after the life of the Buddha the sangha split into two major factions, called Mahasanghika (“of the great sangha”) and Sthavira (“the elders”). The reasons for the Great Schism are not entirely clear, but most likely concerned a dispute over the Vinaya-pitaka, rules for the monastic orders. Sthavira and Mahasanghika then split into several other factions. Theravada Buddhism developed from a Sthavira sub-school that was established in Sri Lanka in the 3rd century BCE.

The detailed development of the different Buddhist schools is difficult to follow because of the lack of sufficient sources. For example, for the initial phase of Buddhism, evidence – like written documents, inscriptions and archaeological elements – is almost completely missing. Unfortunately, all the sources postdate the emergence of the Buddhist schools by several centuries, and cannot be considered fully reliable. The development can be viewed like a series of gradual and small changes, and this could be the reason why records on this matter are virtually non-existent.

The idea of a united and harmonious Buddhist community – from which, after many generations, different sects and schools emerged as a result of gradual fragmentation – is challenged by what traditional sources tell us about disagreements among the Buddha disciples even during his lifetime, and it seems to be clear that the element of dissent was present in the Buddhist community from a very early stage. After the Buddha’s death, the accounts tell about the first council, where a group of early Buddhists rejected the consensual understanding of the teachings of the Master. Over the centuries, more councils will be held, so, more fragmentation will happen.

What is known for sure is that for several centuries after the death of the Buddha, those who followed his teachings had formed settled communities in different locations. The growth and geographical dispersion led to inevitable changes in their methods of both teaching and practices. As the number of members grew, the institutional organization increased its complexity, monks expanded and elaborated both doctrine and disciplinary codes, developed new forms of disciplines, and eventually divided into a number of different schools. Geographical separation, language difference, doctrinal disagreements, selective patronage, the influence of non-Buddhist schools, loyalties to specific teachers, the absence of a recognized overall authority or unifying organizational structure and specialization by various monastic groups in different segments of Buddhist scriptures are just some examples of factors that contributed to sectarian fragmentation. As we said, the main Buddhist schools are:

– Hinayana – Originally eighteen or more schools of which only Theravada exists today. It has a realistic view of existence and suffering; its supreme goal is the liberation from the cycle of rebirth, and attainment of Nirvana through renunciation and leading a monastic life; Hinayana ideal is the Arhat,”worthy one,” who attains complete purification, salvation, freedom from the cycle of existence. Theravada centers around the Pali scriptures, transcribed from the oral tradition taught by the Buddha. By studying these ancient texts, meditating, and following the eightfold path, Theravada Buddhists believe they will achieve Enlightenment.

– Mahayana Buddhism developed out of the Theravada tradition roughly 500 years after the Buddha attained Enlightenment. A number of individual schools and traditions have formed under the banner of Mahayana, including Zen Buddhism, Tibetan Buddhism, Pure Land Buddhism, and Tantric Buddhism. Mahayana Buddhism focuses on the idea of compassion and touts bodhisattvas, which are beings that work out of compassion to liberate other sentient beings from their suffering, as central devotional figures.

– Vajrayana was last of the three ancient forms to develop, and is the on who provides a quicker path to Enlightenment than either the Theravada or Mahayana schools. They believe that the physical has an effect on the spiritual and that the spiritual, in turn, affects the physical. Vajrayana Buddhists encourage rituals, chanting, and tantra techniques, along with a fundamental understanding of Theravada and Mahayana schools, as the way to attain Enlightenment.

– Zen Buddhism is said to have originated in China with the teachings of the monk Bodhidharma. Zen Buddhism treats zazen meditation and daily practice as essential for attaining Enlightenment, and de-emphasizes the rigorous study of scriptures.

Of course, there are other schools, like for example:

– Madhyamika, also known as Middle Way, founded by Nagarjuna, and his disciple Aryadeva; predominately in India, Tibet, China and Japan; the Middle Way position relates to the existence or non-existence of things; “since all phenomena arise in dependence upon conditions, they have no being of their own and are empty of a permanent self.”

– Yogachara – A school of Mahayana Buddhism founded by Maitreyanatha, Asanga, and Vasubandhu, with the position that all experiences and things “exist only as processes of knowing, not as ‘objects;’ outside the knowing process they have no reality….This process is explained with the help of the concept of the ‘storehouse consciousness’” – alaya-vijnana.

– Nyingmapa – Tibetan word meaning “School of the Ancients;” of the four main Tibetan Buddhist schools, the Nyingmapa embraces the oldest Tibetan Buddhist traditions brought from India by Padmasambhava, Vimalamitra, and Vairochana in the 8th century; teachings include mahayoga, anuyoga, and atiyoga (dzogchen).

– Kagyupa – Tibetan word meaning “oral transmission lineage;” emphasis placed on direct transmission of teachings from teacher to disciple; beginning with Tilopa and then Naropa, Marpa the Translator carried these teachings to Tibet, whence his student Milarepa spent years of practice in mastering them.

– Sakyapa – This Tibetan school is named for the Sakya (Gray Earth) Monastery of southern Tibet; originated in 1073; teachings are part of Vajrayana and Tantra; teachers were recognized incarnations of Manjushri; one renowned teacher was Sakya Pandita, known in India and Mongolia.

– Gelugpa – Tibetan for “school of the virtuous;” based on the writings of Tsongkhapa, who received a vision of Manjushri and formulated voluminous commentaries with the Madhyamika (Middle Way) view; spiritual practices of achieving concentration (samadhi), dwelling in tranquility (shamatha), and special insight (vipashyana).

There are other big or small schools or sects, each of them being somehow different than the others. All the schools differ at least in one aspect, but all of them share the same basic principles. All have the same root, Buddha Shakyamuni‘s core teachings.

photo credit : JamesKennedy