Theravada Buddhism is sometimes called ‘Southern Buddhism’. The name means ‘the doctrine of the elders’ – the elders being the senior Buddhist monks.

This school of Buddhism believes that it has remained closest to the original teachings of the Buddha. However, it does not over-emphasise the status of these teachings in a fundamentalist way – they are seen as tools to help people understand the truth, and not as having merit of their own.

Theravada beliefs

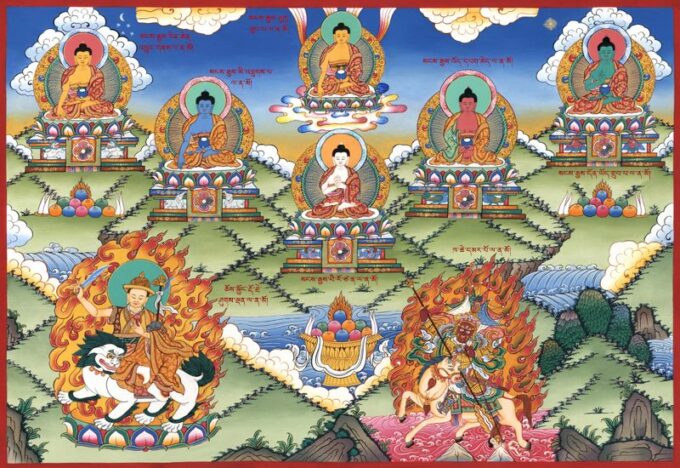

- The Supernatural: Many faiths offer supernatural solutions to the spiritual problems of human beings. Buddhism does not. The basis of all forms of Buddhism is to use meditation for awakening (or enlightenment), not outside powers. Supernatural powers are not disregarded but they are incidental and the Buddha warned against them as fetters on the path.

- The Buddha: Siddhartha Gautama was a man who became Buddha, the Awakened One . Since his death the only contact with him is through his teachings which point to the awakened state.

- God: There is no omnipotent creator. Gods exist as various types of spiritual being but with limited powers.

- The Path to Enlightenment: Each being has to make their own way to enlightenment without the help of God or gods. Buddha’s teachings show the way, but making the journey is up to us.

Theravada life

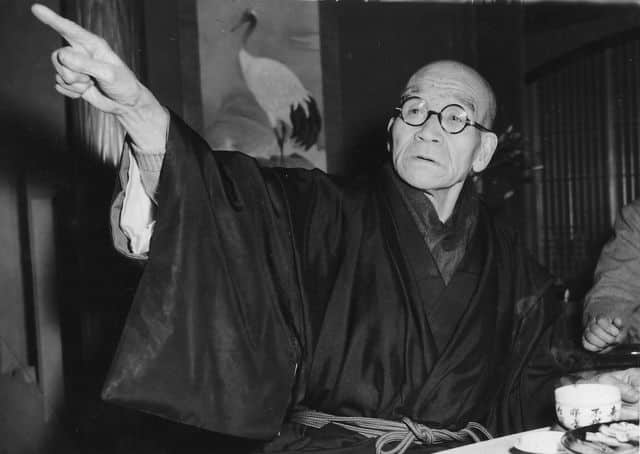

Theravada Buddhism emphasises attaining self-liberation through one’s own efforts. Meditation and concentration are vital elements of the way to enlightenment. The ideal road is to dedicate oneself to full-time monastic life.

The follower is expected to “abstain from all kinds of evil, to accumulate all that is good and to purify their mind”.

Meditation is one of the main tools by which a Theravada Buddhist transforms themselves, and so a monk spends a great deal of time in meditation.

When a person achieves liberation they are called a ‘worthy person’ – an Arhat or Arahat.

Despite the monastic emphasis, Theravada Buddhism has a substantial role and place for lay followers.

Monastic life

Most Theravada monks live as part of monastic communities. Some join as young as seven, but one can join at any age. A novice is called a samanera and a full monk is called a bikkhu.

The monastic community as a whole is called the sangha.

Monks (and nuns) undertake the training of the monastic order (the Vinaya) which consist of 227 rules (more for nuns). Within these rules or precepts are five which are undertaken by all those trying to adhere to a Buddhist way of life. The Five Precepts are to undertake the rule of training to:

- Refrain from harming living beings

- Refrain from taking that which is not freely given

- Refrain from sexual misconduct

- Refrain from wrong speech; such as lying, idle chatter, malicious gossip or harsh speech

- Refrain from intoxicating drink and drugs which lead to carelessness

Of particular interest is the fact that Theravadan monks and nuns are not permitted to eat after midday or handle money.

Theravada life

Meditation

Meditation is impossible for a person who lacks wisdom. Wisdom is impossible for a person who does not meditate. A person who both meditates and possesses wisdom is close to nibbana.

The Theravada tradition has two forms of meditation.

- Samatha: Calming meditation

- Vipassana: Insight meditation

Samatha

This is the earliest form of meditation, and is not unique to Buddhism. It’s used to make the mind calmer and take the person to higher jhanic states. The effects of Samatha meditation are temporary.

Vipassana

This form of meditation is used to achieve insight into the true nature of things. This is very difficult to get because human beings are used to seeing things distorted by their preconceptions, opinions, and past experiences.

The aim is a complete change of the way we perceive and understand the universe, and unlike the temporary changes brought about by Samatha, the aim of Vipassana is permanent change.

Lay people and monks

The code of behaviour for lay people is much less strict than that for monks. They follow the five basic Buddhist principles.

A strong relationship

The relationship between monks and lay people in Theravada Buddhism is very strong. This type of Buddhism could not, in fact, exist in its present form without this interaction. It is a way of mutual support – lay people supply food, medicine, and cloth for robes, and monks give spiritual support, blessings, and teachings. Monks are not allowed to request anything from lay people; and lay people cannot demand anything from the monks. The spirit of it is more in the nature of open-hearted giving. The system works well and is so firmly established in most Theravadan countries that monks are usually amply provided for, depending on the wealth or poverty of the local people.

Ceremonies and commemoration days

There are numerous ceremonies and commemoration days which lay people celebrate, such as Wesak which marks the birth, enlightenment, and parinibbana (passing away) of the Buddha, and for these events everyone converges on the local temples.

Retreats

Monasteries often have facilities for lay people to stay in retreat. The accommodation is usually basic and one has to abide by Eight Precepts (to abstain from killing, stealing, engaging in sexual activity, unskilful speech, taking intoxicating drink or drugs, eating after midday, wearing adornments, seeking entertainments, and sleeping in soft, luxurious beds).

Texts

The fundamental teachings were collected into their final form around the 3rd century BCE, after a Buddhist council at Patna in India. The teachings were written down in Sri Lanka during the 1st century CE. They were written in Pali (a language like Sanskrit) and are known as the Pali canon. It’s called the Tripitaka – the three baskets. The three sections are:

- the Vinaya Pitaka (the code for monastic life) These rules are followed by Buddhist monks and nuns, who recite the 227 rules twice a month.

- the Sutta Pitaka (teachings of the Buddha) This contains the whole of Buddhist philosophy and ethics. It includes the Dhammapada which contains the essence of Buddha’s teaching.

- the Abhidhamma Pitaka (supplementary philosophy and religious teaching) The texts have remained unaltered since they were written down. Buddhist monks in the Theravada tradition consider it important to learn sections of these texts by heart.

Although these texts are accepted as definitive scriptures, non-Buddhists should understand that they do not contain divine revelations or absolute truths that followers accept as a matter of faith. They are tools that the individual tries to use in their own life.

Source: deathandreligion.plamienok.sk photo credit : shin-ibs.edu