The Zen Poet Ryokan Taigu (1758–1831) is one of the most beloved figures of Japanese Soto Zen, regarded also as one of the greatest poets of the Edo Period, along with Basho, Buson, and Issa.

After completing rigorous training in a monastery for ten years, Ryokan choosed to live mostly as a hermit and a beggar. He was never head of a monastery or temple. He drifted back to his native place, and remained there the rest of his days, living quietly in mountain hermitages. He supported himself by begging, sharing his food with birds and beasts, and spent his time doing Zazen, gazing at the moon, playing games with the local children and geishas, visiting friends, drinking sake with farmers, dancing at festivals and composing poems brushed in exquisite calligraphy.

There are numerous anecdotes about Ryokan

There are numerous anecdotes about Ryokan good humor, compassion and unselfishness. Yoshishige Kera, author of Anecdotes of Zen Master Ryokan, who knew the monk in his youth, described him as it follows:

“The master was full of lofty spirit, which was naturally expressed. He was tall and slender, like a Daoist sorcerer, with a high nose and long eyes. He was gentle, stern, and not presumptuous. . . . Ryokan did not show excitement or anger. I never heard him speak fast. His way of eating and drinking was slow, almost like a fool.”

Portrait and calligraphy

According to Kera’s Anecdotes:

“Ryokan had uncombed hair and an unshaven face, walked barefoot and wore a torn robe. He would go into people’s kitchens and beg food.

Once when he visited a house, something valuable was stolen. People in the house thought Ryokan was the thief, escaped from the local prison. They summoned the villagers by blowing a conch shell and hitting a wooden board.

The villagers bound him with a rope and tried to bury him alive. But Ryokan did not say a word, letting them do what they wanted. Before they threw him into a hole, someone who knew Ryokan noticed them and said, “What are you doing? This is the famous Zen master Ryokan. Untie the rope right away and apologize to him.”

Astonished, the villagers did so. The person who rescued him said, “Why didn’t you say that it was a false accusation? Ryokan said, “All the villagers suspected me. Even if I had explained, that wouldn’t have removed their suspicion. There is nothing better than saying nothing.”

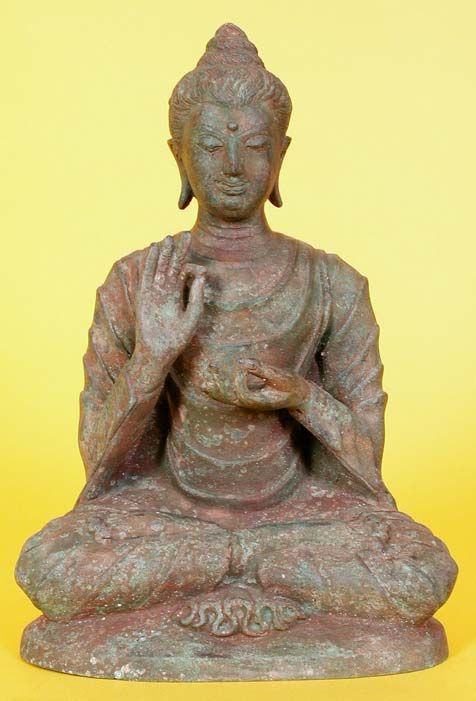

Statue of Ryōkan from the Ryūsen-ji temple in Nagaoka, Niigata.

Other anecdote tells us that he used to pick the lice from his robe in the warm spring and place them on a rock to sun themselves. At the end of the day, as night began to fall, he took them from the rock and placed them back on his robe.

Answering a young monk who complained that Ryokan ate fish, he said, “I eat fish when offered, but I also let the fleas and mosquitoes feed on me”. He used to sleep, according the stories, with one leg outside a mosquito net, so that the bugs would have food and he would not roll on them in his sleep.

The samurai lord of the local domain heard of Ryokan’s reputation as a worthy Zen monk and wanted to construct a temple and install Ryokan as abbot. The lord went to visit the monk at Gogō-an, his hermitage on Mount Kugami, but he was out gathering flowers, and the party waited patiently until Ryokan returned with a bowl full of fragrant blossoms. The lord made his request, but the monk remained silent. Then he brushed a haiku on a piece of paper and handed it to the lord:

And, maybe, the most famous story about this eccentric and beloved Zen Master:

“One night a thief entered into Ryokan’s small hut. Ryokan had only one blanket which he used day and night to cover his body. That was his only possession. He felt great compassion for the thief because he knew there was nothing in the house. ‘If the poor fellow had informed me before, I could have begged something from the neighbours and kept it here for him to steal. But now what can I do?’

Seeing that there was nothing, that he had entered into a monk’s hut, the thief went out. Ryokan could not resist. He gave his blanket to the thief. When the thief left, he wrote the famous haiku in his diary:

Cartoon from the book “Zen Speaks” by Tsai Chih Chung

Ryōkan wrote thousands of poems and poem-letters, both Chinese and Japanese style. We selected ten of them below:

how do you know it was not wrong yesterday? There is no right or wrong, no predicting gain or loss. Unable to change their tune, those who are foolish glue down bridges of a lute. Those who are wise get to the source but keep wandering about for long. Only when you are neither wise nor foolish can you be called one who has attained the way. You see the moon by pointing your finger. You recognize the finger by the moon. are not different, not the same. In order to guide a beginner, this analogy is temporarily used. When you have realized this, there is no moon, no finger. about the mind of this monk, a passage of wind

in the vast sky. Without desire everything is sufficient. With seeking myriad things are impoverished. Plain vegetables can soothe hunger. A patched robe is enough to cover this bent old body. Alone I hike with a deer. Cheerfully I sing with village children. The stream beneath the cliff cleanses my ears. The pine on the mountain top fits my heart. Within this serene snowfall flurries come floating down. Fresh morning snow in front of the shrine, The trees! Are they white with peach blossoms The children and I joyfully throw snowballs. On a quiet evening in my thatch-roofed hut, alone I play a lute with no string. Its melody enters wind and cloud, mingles deeply with a flowing stream, fills out the dark valley, blows through the vast forest, then disappears. Other than those who hear emptiness,who will capture this rare sound?

Nothing is reliable; everything must change. You hold on to letters and names in vain, forcing yourself to believe in them. Stop chasing new knowledge. When there is nothing left to see through, then you will know your mistaken views. Great is the robe of liberation, a formless field of benefaction. Buddhas have authentically transmitted it. Ancestors have intimately received it. Beyond wide, beyond narrow, beyond cloth, beyond threads; then you are called a keeper of the robe. What legacy shall I leave behind? Flowers in spring. Cuckoos in summer.

Maple leaves in autumn.

Futher reading about Master Ryokan:

- Dew-Drops on a Lotus Leaf (Ryokwan of Zen Buddhism), foreword and translation by Gyofu Soma & Tatsukichi Irisawa. (Tokyo, 1950)

- Sky above, great wind: the life and poetry of Zen Master Ryokan / Kazuaki Tanahashi.

- One Robe, One Bowl; The Zen Poetry of Ryōkan, 1977, translated and introduced by John Stevens. Weatherhill, Inc.

- Three Zen Masters: Ikkyū, Hakuin, Ryōkan (Kodansha Biographies), 1993, by John Stevens.

- The Zen Fool: Ryōkan, 2000, translated, with an introduction, by Misao Kodama and Hikosaku Yanagashima.

- Great Fool: Zen Master Ryōkan: Poems, Letters, and Other Writings, 1996, by Ryuichi Abe (with Peter Haskel).

- Ryokan: Selected Tanka and Haiku, translated from the Japanese by Sanford Goldstein, Shigeo Mizoguchi and Fujisato Kitajima (Kokodo, 2000)

- Ryokan’s Calligraphy, by Kiichi Kato; translated by Sanford Goldstein and Fujisato Kitajima (Kokodo, 1997)