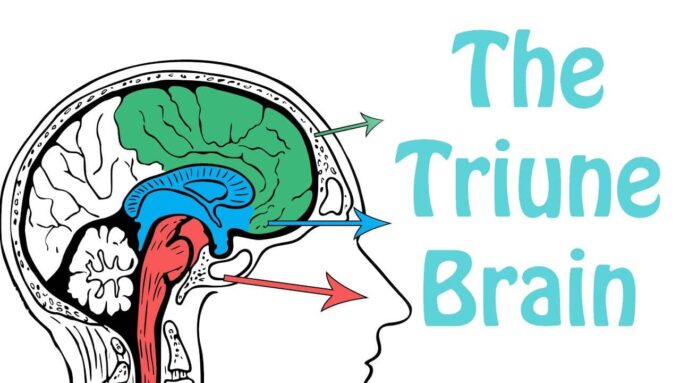

It can be helpful to remember that the brain, this organ each of us carries inside our skull, is the product of 650 million years of evolution. Probably the best-known model for understanding the structure of the brain in relation to its evolutionary history is the famous triune brain theory, which was developed by Paul MacLean and became very influential in the 1960s.

The division of the brain into three parts constitutes what MacLean calls the Triune Brain of mammals (meaning three brains in one). This conceptualization represents a hierarchical organization of the brain from an evolutionary perspective.

In the 1950s, the American physician and neuroscientist Paul MacLean proposed a theoretical model for how the brain worked – that he called the “triune brain.” MacLean originally formulated his model in the 1960s and propounded it at length in his 1990 book The Triune Brain in Evolution. His theory was based on the idea that our brain evolved in three stages so that we essentially have not one but three brains inside our head: the reptilian brain, the paleomammalian complex (the limbic brain), and the neomammalian complex (the neocortex). Contemporary neuroscience has replaced many specifics of MacLean’s theory, but his triune brain is still a helpful way to understand the structures of the brain and how they influence human behavior.

The reptilian brain is the oldest part of the brain. It is responsible for muscle movement, balance, and basic autonomic functions like heart rate, blood pressure, and respiration. It includes the brain stem and the cerebellum, which tend to dominate in reptiles. In terms of behavior, this part of the brain is aggressive, territorial, compulsive, and doesn’t learn from mistakes. The limbic or mammalian brain is the primary seat of emotions, attention, and emotionally charged memories, and it tends to be predominant in mammals. Instincts such as feeding, fighting, fleeing, and sexual behavior are rooted here, as well as our instinctual, social, and emotional needs to feel connected, calm, and cared for.

Structurally, the limbic brain includes the hypothalamus, the master gland, which manufactures both oxytocin and CRH (Corticotropin-releasing hormone), the precursor to the cascade of hormones that eventually results in adrenaline production; the hippocampus, which compares external images to stored memories; and the amygdala, which sends the signal to flood the body with the chemicals of fight or flight when the hippocampus senses danger.

The third part of the brain, the neocortex, and especially the prefrontal cortex or neomammalian brain, is the newest of the three. It’s responsible for what we think of as our higher cognitive functions, such as abstract reasoning, language, enhanced learning and memory, introspection, and insight. This is the part of our brain that rehearses and worries about the future, rehashes and analyzes the past, makes plans and reasoned arguments, and attempts to solve problems.

All three parts of our brain are interconnected by a vast network of neurons. Though we might like to believe that the newest part of our brain, the more rational, “thinking” neocortex, is in charge, in fact it seems that the limbic system, the seat of our emotions, can all too easily dominate our behavior. (Road rage is a perfect example of this.) Together the three areas of the brain shape our experience from the bottom up as we go about daily life, learning from and attuning to each other and our surroundings according to the patterns of our culture, our language, our unique personal and emotional history, and our temperament, all of which contribute to our view of ourselves and the world in which we live.

MacLean hypothesized that these three “complexes” not only represented three distinct stages of brain evolution, but remained three separate, semi-independent brains, “[each] with its own special intelligence, its own subjectivity, its own sense of time and space and its own memory.” MacLean was saying, in other words, that every human brain contains three independent subjective consciousnesses.

It has been suggested that a breakdown in communication among the parts of the triune brain is responsible sometimes for pathological behavior. An example would be the split between rational thought and emotion found in schizophrenia. More commonly, most of us have probably experienced, at one time or another, what might represent a relatively minor and temporary occurrence of a neuro communication breakdown. Specifically, it happens when we suddenly explode in an outburst of emotion while at the same time our rational mind is conscious of the event but incapable of bringing the behavior under control. In that moment, we may feel as if we are two individuals in one: that which is doing the acting, the paleomammalian and proto-reptilian brain, and that which is passively observing, the rational neomammalian brain. Perhaps the prefrontal link between the neocortex and limbic system (which is the major connection between these two divisions of the brain) gets temporarily blocked due to hyperactivity in the paleomammalian brain when we are unusually emotionally aroused. As a result, the rational brain cannot regulate our emotional, instinctive behaviors.

MacLean has proposed that rather than the rational, neomammalian brain, it is the paleomammalian brain, the seat of emotion, that is responsible for perceptions of what is true, i.e., what is reality. It is the paleomammalian brain, moreover, that is responsible for the feelings of oneness with the universe that are associated with ecstatic, mystic, religious, and drug states (as demonstrated by the aura of psychomotor/ temporal lobe-limbic system epilepsy).

MacLean believes that the most fundamentally important philosophical implication of his work is that our so-called “rational” perceptions of truth are merely neocortical rationalizations for feelings welling up from the limbic system–the seat of emotion.

However, this triune hypothesis is no longer espoused by the majority of comparative neuroscientists in the post-2000 era. The research showed that the three parts of the brain do not operate independently of one another. They have established numerous interconnections through which they influence one another. The neural pathways from the limbic system to the cortex, for example, are especially well developed. The current trends in understanding the neurocognitive function, and all brain function are based on theories of connectivity, on neural networks and systems integration.

Photo credit: bible.ca