*by Norman Fischer (originally published at Buddhadharma Magazine – Spring 2014.)

From the beginning, Norman Fischer never had much use for Zen teachers—and he still doesn’t. But after years of being one himself, he has a fuller appreciation of the role a teacher plays.

One of my favourite Zen stories is about teachers. The great Zen teacher Huangbo strides into the hall and says to the assembled monastics, “You people are all dreg-slurpers! If you go on like this, when will you ever see today? Don’t you know that in all of China, there are no teachers of Zen?”

A monastic comes forward and says to him, “Then what about all those people like you who set up Zen places that students flock to like birds?” Huangbo replies, “I don’t say there is no Zen, only that there are no teachers.”

As an independent-minded (some would say stubborn) person, I find this story appealing. I have never been attracted to Zen masters or gurus, powerful and charismatic spiritual guides. There may or may not actually be such special people, but in any case, I have never been interested in them. I assume that I know what I need to know for living my life, and that when I need to know more I will find it out for myself. No wisdom or experience that isn’t my own is worthwhile.

So I have asked myself, what’s the point of spiritual teachers? What benefit could possibly be gained from hanging around some supposed sage if somebody else’s enlightenment is never going to rub off on me?

When I began my Zen study, I wanted to learn how to do zazen so I could find out firsthand what Zen was all about. I was happy to listen to talks and instructions that might help orient me to the practice. But the idea that following a Zen teacher and hanging on his every word and deed (in those days, Zen teachers were men) would somehow help me become enlightened seemed not only unappealing but also wrong.

My thoughts resonated with Huangbo’s: there is Zen, but there are no teachers of Zen. Of course, people with credentials set up shop and welcome students. We all need some structure and a place to practice. But the teacher can’t teach you. Your practice is up to you. Good old American individualism. I believed it so much that I had no interest whatsoever in encountering teachers, though at the time there were several storied Asian Buddhist teachers in America. Though I first came to San Francisco Zen Center in the summer of 1970, about a year and a half before the passing of the center’s great founder, Shunryu Suzuki Roshi, I made no effort to hear him speak, never saw him, and was not interested in attending his funeral nor the installation of his successor, the first American Zen master, that preceded it. Looking back at this now, I see it as a missed opportunity. But that’s how I was at the time.

All this might imply that I was a rebellious Zen student. But I wasn’t. I had no problem respecting my teachers, listening to their talks, going for regularly scheduled interviews. To reflexively rebel, challenge, or deny a teacher is to set up a teacher in your mind who fulfils the ideal requirements the teacher in front of you is failing to fulfil. If you feel compelled to rebel, it is probably because you actually do believe in an idealized almighty Zen master. I had no such belief and no such compulsion. I was at the Zen Center to study Zen. I had my reasons for wanting to do that. Since the teachers were in charge, I would cooperate with them. But whatever benefit or understanding or enlightenment I got was my own affair. No one else could give it to me or even lead me to it.

I recount all this not because I entirely agree with it now, but to give a sense of how I was thinking about teachers and Zen practice in my early years. I certainly did not think that I would become a Zen teacher myself. My thought was simply to get what I needed from the practice and move on with my vague life as a poet, surviving somehow. My wife, Kathie, and I were ordained as Zen priests in 1980 because our teacher required us to either do that and continue to practice at the centre full-time or move on and get a life (we had two children by then). We weren’t ready to go, so we agreed to ordain, a step Kathie was much more ready for than I was, but I managed.

In 1988, when my teacher offered me shiho (dharma transmission), which would give me full ordination as a Soto Zen priest, I was surprised. In those days in American Zen, shiho was rare (though it was not rare in Japan). People presumed that only deeply enlightened people could receive it, which is why I was surprised. Nevertheless, I went ahead with the process and became a Zen teacher, a role I found at first disturbing, being so ill prepared and ill suited for it. But eventually, thinking of Huangbo, I came to accept the social designation “Zen priest” or “Zen teacher,” and since then I have done my best to try to help people practice.

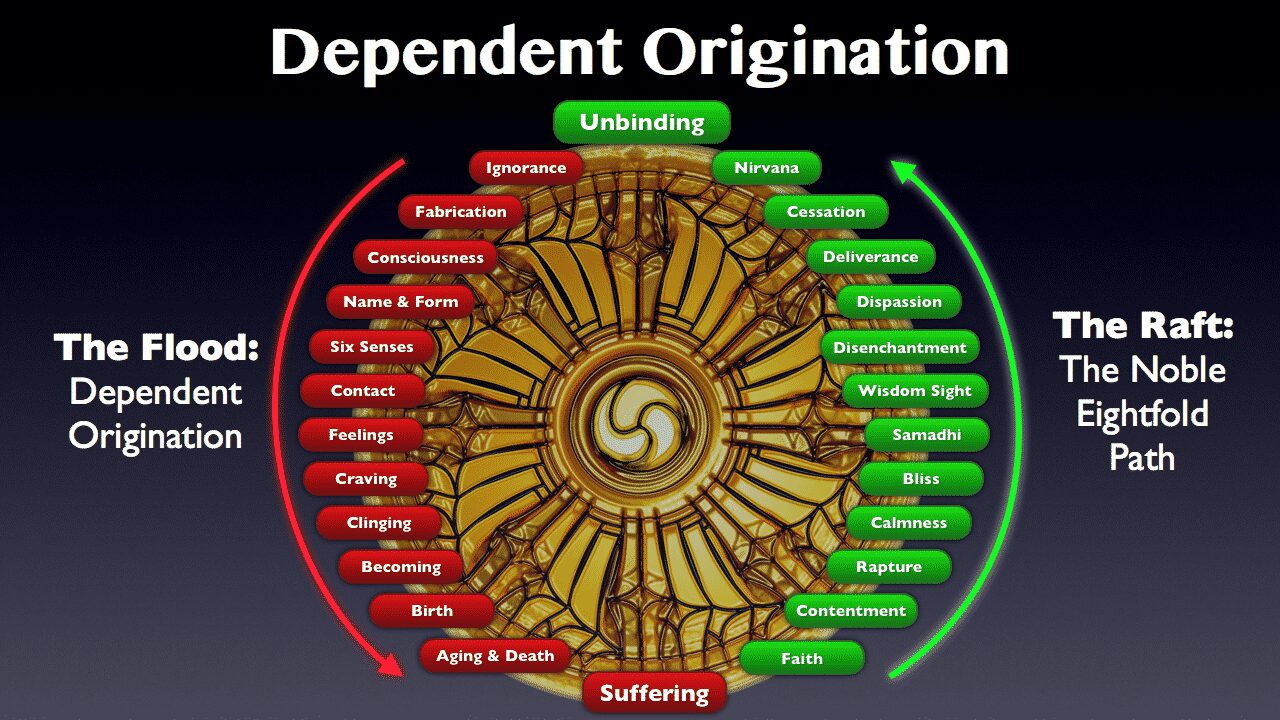

There is more to “no teachers of Zen” than meets the eye. I still believe that students are responsible for their own practice and their own awakening. No one can communicate a truth worth knowing; the only worthwhile truth is the one you find uniquely, for your own life. On the other hand, Zen is not Lone Ranger practice. Zen teachers are important to the practice, as the tradition certainly indicates and experience proves. Yes, there are no Zen teachers because Zen isn’t a teachable subject matter or skill. There are things to be learned, such as Zen liturgy, how to comport one’s self in a zendo, and how to strike a proper bell at a proper time, but it is clear that Zen itself, while not exactly something other than these things, isn’t the same as them. Zen is much more slippery than that. The Heart Sutra says, “All dharmas are empty.” Zen is empty—empty of content, empty of doctrine, style, or faith that can be codified and defined. So what is there to teach?

But yes, there are Zen teachers because Zen practice is not nothing: real transformation occurs. Zen teachers can’t show you how to effect this transformation, they cannot cause it to happen in you, and they are not “masters” of it (no one could be a master of an indefinable, empty feeling for living). But they do play an essential role.

In the ordinary educational model, there are teachers who teach, students who learn, subject matter, standards of knowledge, and an educational institution that contains and certifies the educational process. While in some ways Zen might look like this, in fact Zen is not an educational process but rather a transformational one in which both teacher and student fully engage, each playing his or her proper role. The process itself effects the transformation.

Think of it as a machine with many moving parts that interact in a complex system, each part affecting every other part. No one part “teaches” while another “learns.” Yet run the machine for a while and something happens: a product is produced, in this case a seasoned Zen practitioner who embodies, in his or her own unique way, the values, the commitments, and, mostly, the feeling and vision of a life of practice. So it’s just as Huangbo says: there is Zen but, strictly speaking, no teachers, although yes, the machine won’t turn unless all the parts function fully in their proper places. The teacher, not actually teaching anything, must occupy his or her place in the process. Another analogy might be a mandala: each element has its crucial place in the overall design, but no element is sovereign. Only the overall design matters. So yes, in just this way, teachers are important.

In order to effectively take his or her place in the pattern, the teacher, ideally, has certain capacities. Faith in the practice, especially. And not just enthusiastic faith, but faith grounded in experience over time—faith that is not only spoken of but also demonstrated in action. Experience in the lived reality of the practice is the source of this kind of faith, that certain knowing, to the very bones, that the practice is the truest way to live. “Practice” doesn’t mean only formal practice that happens in temples and meditation halls. It means understanding and living a human life among others. Meditation is fairly new in Western culture, and naturally we have overemphasized it, romanticizing the mystical experiences intensive meditation can produce. Such experiences are just a matter of course. They are among the least important things for a teacher to have experienced, but any Zen teacher will have experienced many such things. Sit there long enough and everything is bound to occur. But it isn’t the experiences that matter as much as the folding of them into a whole life and a whole view.

But even this depth of faith, though essential and basic, is not sufficient. Ideally, a Zen teacher is also willing and able to share life completely with others. This takes a wide and deep acceptance of and interest in the many wily and wild manifestations of the human heart that arise in the course of practice over time. Practice with people for a while and you will bear witness to births, deaths, marriages, divorces, love affairs, enlightenment experiences, endless tears, tragic illnesses, angry feuds, breaches, collapses, and surprises of all sorts. A Zen teacher will eventually live through with others almost everything human beings perpetrate, so he or she needs long patience, deep forbearance and forgiveness, and a healthy sense of the immense tragedy and beauty of human life. The more the teacher has an idea of “Zen” that students must conform to, the more everyone (teacher included) will suffer, if not at first, then later on as people who were initially inspired by that idea come to feel oppressed or even betrayed by it. No doubt there are many important skills people would like their Zen teachers to have, but deep faith and a willingness to share your life honestly are the core of what I have come to feel is most important after having been in this business a long time. But I have also seen Zen teachers who seem seriously lacking in these capacities still be of benefit to others. There seem to be no universal prescriptions in Zen or in life.

Zen practice is dialogic, interactive. Compared to other forms of Buddhism it is, classically, “together practice.” In a formal Zen meal, for instance, everyone starts and ends together. In Zen walking meditation, everyone walks together in single file, evenly spaced. Meditation is done side by side, in a hall, with each period of meditation starting and ending with everyone together. The form of the characteristic literature is also dialogic, with short verbal or nonverbal encounters between teachers and disciples, or disciples and disciples, presenting rough-and-tumble back-and-forth conversations in which the teachings are explored not so much discursively but dynamically, using as few words as possible. And one of the characteristic and essential Zen practices is the one-on-one meeting with the teacher, which is viewed not as reporting in or asking for advice but as “dharma encounter”—a chance to meet oneself by meeting another.

Given this radical “together” style, it’s clear that a Zen teacher has to be ready, all the time, to let go of his life and enter the life of the other. This deep mutuality is the essence of the Zen process. It’s been wonderful training for a stubborn person like myself, softening me considerably over the years and expanding my horizons. But it took me a while to be ready for this or even to know that it was required. Soon after my shiho ceremony in 1988, I read a line in one of Thich Nhat Hanh’s books to the effect that “if you can’t find a true teacher, it is best not to study.” This tangled me up for a while in the net of my unacknowledged preconceptions about Zen teachers. I found it very upsetting because it seemed to imply some exalted state of being a “true teacher,” a state unknown to me.

Yet here I was, one of the few American Zen people in those days with full dharma transmission, and what did I think I was doing? It took me a few uncomfortable years to finally catch up with Thich Nhat Hanh to ask him about this, and he told me something like, “Don’t worry, we all help each other. The one-day person helps the one who just came in the door. The five-year person helps the one-year person. Each one helps according to his experience.” That made me feel much better.

Still, it took me years to feel comfortable in the teacher’s seat. (And being a so-called Zen teacher is, in many ways, literally that, feeling comfortable in the seat you are sitting in, facing the altar, at the front of the zendo.) For a while I was unconsciously caught by the idea that I was supposed to be someone that others expected me to be, and I couldn’t help but strain a bit to be that person. But the truth is, there was no one in particular I needed to be.

A formal Zen talk isn’t conceived of as a lecture on Zen; it’s called “presenting the shout”— that is, expressing the teaching just by speaking in your own voice. I have always appreciated the fact that when you give a Zen talk, you make three prostrations to the Buddha before and after the talk. These bows are meant to indicate that it isn’t exactly you giving the talk. The Buddha is giving the talk using your body and voice. Bowing is praying to Buddha to help you do as good a job at channeling him as you possibly can, with the faith that whatever you say, right or wrong, will be of some use if you are sincere and try your best. After some years I came to see that this applied to anything I did as a Zen teacher: if I was honest, tried my best, followed precepts, and didn’t pretend to be anyone, everything would be okay. This sounds simple-minded enough, and it is, but it is actually not so easy to do.

And what does “everything would be okay” actually mean? It certainly doesn’t mean that things won’t ever go wrong. In fact, things will certainly go wrong. Maybe another capacity a Zen teacher should develop is the resilience and breadth of view that will enable her to live with the fact that she is going to fail. At least, this has been my experience. Occupying the teacher gear in the whirling Zen machine requires that you receive everything with an open heart and have the willingness and stamina to take full responsibility for each and every relationship you enter, which means to care and try your best to help.

People come to Zen practice, as they do to any spiritual practice, with plenty of human needs. They come with trust, mistrust, and hidden expectations. Of course, the Zen teacher, an imperfect human being, is going to disappoint a fair number of them. Some will be disappointed on the first day, others only after many decades. You, the teacher, will misunderstand them and they will misunderstand you. You will say and do things that are hurtful, even if you never intended to. Meaning to straighten someone out (always a dubious proposition), you will completely botch the job, reinforcing the behavior or view you were trying to soften. Students who have practiced faithfully with you for years will realize it has all been wrong and leave, creating confusion and dissension. Your public words and actions will, in being variously understood and misunderstood, create confusion among sangha members who will act out their confusion in sometimes painful ways. You will have all kinds of complicated and contradictory feelings about people who come to practice with you—loving them, worrying about them, dreading them, seeing them make terrible mistakes you can’t prevent, watching as they manipulate you and set you up for all sorts of falls. In the end, you will realize you can’t help them at all and will have to watch them suffer, or watch them make you suffer, and maintain your composure even so.

I have spoken to many Zen teachers who are trying hard to get better at what they do—to see where they make mistakes and to correct those mistakes, maybe even to get some psychological or other training so they can understand the various twisted ways students sometimes present themselves. I have learned from commiserating with other teachers (something I think is essential) and from my many mistakes. Ultimately, I think Zen teachers can no more learn than teach. Each situation, each person, is unique, and one’s own response, at that time, to that person, must and will inevitably be unique. I always trust my response and am, of course, willing to change or be corrected when proven wrong. But in the end, I know I’ll never get it right. Sometimes getting it wrong is the best thing anyway.

It’s true that everything always turns out okay. When you really trust the process of the practice more than you trust your limited self, the limited sangha, or what happens in the short run, you realize that the magic of the practice is much stronger than you thought. It is not limited to what you or anyone says or does; it is not limited to meditation or what takes place in meditation halls or on temple grounds.

I have seen how after leaving a place of practice in a huff or not in a huff, students’ lives miraculously turn around, sometimes five, ten, or twenty years later, because of unexpected circumstances that Buddha somehow placed in the middle of their lives long after they left. Sometimes the perfect priest you thought you were ordaining needs to fall apart, leave, and go through many ups and downs for decades before she finally emerges as the Buddha you always knew she was. Or the wreck of a human being who was so disruptive and annoying and hopeless comes back to visit you decades later shining with love. And the crazy mixed-up young woman who seemed headed for certain doom returns with her three lovely children, grateful for the practice she seemed to have resisted mightily at the time.

Seeing things like this happen over and over again, you do come round, finally, to trusting the practice—and life. This helps you trust yourself and the basic goodness of everyone you practice with. The secret ingredient in teaching Zen, it turns out, is the brilliant spark of human goodness in each person. Practice awakens it, and it does the rest on its own eventually. You, the teacher, just have to be willing to be there, and be surprised.

*Zoketsu Norman Fischer is an American poet, writer, and Soto Zen priest, teaching and practicing in the lineage of Shunryu Suzuki