The Sanskrit word Samsara refers to the wheel of life, the cycle of birth, death, and rebirth. These meanings are evident in this non-narrative documentary directed by Ron Fricke and produced by Mark Magidson. Fricke says that the perpetual cycle of everything is the subject of this movie.

Samsara was shot over the course of five years in twenty-five countries on five continents. Ron Fricke and his producer and co-editor Mark Magidson dragged their 70-millimeter cameras to some of the remotest areas of the world, covering 100 locations, resulting in images that have an amazing combination of massive scale and detailed texture. There are aerial shots of the temple complex at Pagan in Myanmar, views of an elaborate mandala being created at a Tibetan monastery in Ladakh in India, some time-lapse photography of the Los Angeles freeways, bustling cities and spartan villages, cloistered mountain monasteries and beautiful sand dunes, sacred sites, and religious rituals.

The content of Samsara is varied. It’s a film without dialogue or script in the conventional sense – being comprised almost exclusively of visuals and music. Samsara’s creators call it a “meditation” or a “non-verbal film”. With amazing cinematography and mesmerizing music, the film enable us to see and feel the distress of Earth and humankind, so that we understand that the healing of self and the healing of the planet are linked together.

The filmmakers take us on a quest to a greater understanding of the human condition and appreciation the beauty and power of the natural world. We see poverty and suffering when people of the Third Ward in New Orleans cleaning up after Katrina, youngsters and elders searching in garbage dumps full of toxic computer parts, gaunt and angry children in large city slums, soldiers standing guard with rifles and clenched fists, scowling African tribesmen wary of intruders, a geisha girl shedding a tear, prostitutes in Thailand, factory workers creating sex dolls.

But we can also see the delicate beauty of traditional Balinese dancers, the tide seen from the top of Mont St. Michael, the chandeliers in Chateau de Versailles, how the light changes over red rock landscapes in Arches National Park in Utah, the majestic waterfalls at Epupa Falls, Angola, islands amidst turquoise waters, the enchanting fields and temples in Bagan, Myanmar, the ornate art on cathedral ceilings, the 1,000 Hand Goddess dancers in Beijing, China.

The spirit of war is also present. We see guns, violence, hatred, and war: grim-faced African warriors, robotic marching soldiers on parade, proud gun-owners and users, a scarred war hero, factory workers making guns and bullets, a family burying someone in a casket shaped like a handgun.

Some images reveal a pervasive indifference to the poor people and a lack of respect for anything. The gap between the rich and the poor is obvious as penthouses with their own swimming pools are contrasted with scenes of children sitting on bricks in garbage strewn houses. We can see workers being forced to carry back-breaking loads at a sulphur mine while others do repetitive work in huge factories.

Samsara is about life and death, but it also presents the factors and forces which can lead to rebirth and personal transformation. The filmmakers put before us a mix of devotional rituals and practices: a baptism taking place in Divine Savior Church in San Paulo, Muslims praying in various mosques around the world, Hasidic Jews praying at the Western Wall, an awesome overview shot of Muslim pilgrims circumambulating the Kaaba in Mecca.

With its visual variety and beauty, its spiritual and religious messages, its celebration of the natural world, its critique of war and all the factors that fuel hatred and violence, and its subtle efforts to help us see our oneness with the human family and the whole of creations, Samsara is in itself a profound spiritual experience. It piles on so many pointed tableaux of a technologically routinized (and implicitly soulless) society that it begins to resemble an inexorable machine itself.

Samsara is not only a visual masterwork; it also has an incredible musical score by Michael Stearns, Lisa Gerrard, and Marcello de Francisci comprised of many different types of devotional music, religious and spiritual chants, and meditative orchestrations.

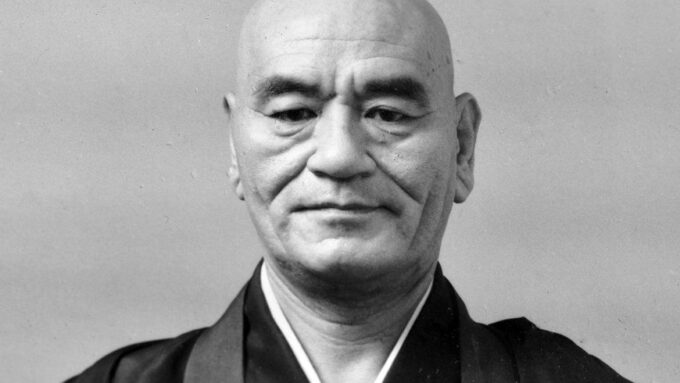

Samsara’s director and cinematographer, Ron Fricke, is known as an expert visual stylist (he is also the director of another famous movie – Baraka), and his capabilities are on full display, without using the CG technology. Fricke and Magidson rely on motion-control and time-lapse photography to take what could be ordinary images and infuse them with an extraordinary quality.

~ The pair (Ron Fricke and Mark Magidson) had collaborated on Baraka (1992) and reunited in 2006 to plan Samsara. They researched locations that would fit the conceptual imagery of samsara, to them “meaning ‘birth, death and rebirth’ or ‘impermanence’”. They gathered research from people’s works and photo books as well as the Internet and YouTube, resources not available at the time of planning Baraka. They considered using digital cameras but decided to film in 70 mm instead, considering its quality superior. Fricke and Magidson began filming Samsara the following year. Filming lasted for more than four years and took place in 25 countries across five continents. Three years into filming, the pair began assembling the film and editing it. They pursued several pick-up shoots to augment the final product. ~ wikipedia

The film doesn’t comment. It just observes, presenting the facts. The filmmakers say the ending is intended to be ambiguous, but the poignant message of the movie is about the beauty, fragility, and impermanence of life and about how everything is linked together.

photo credit: samsara

Trailer

Full movie