Tibetan Buddhism, usually understood as including the Buddhism of Tibet, Mongolia, Bhutan and parts of China, India, and Russia, combines the essential teachings of Mahayana Buddhism with Tantric and Shamanic, and material from an ancient Tibetan religion called Bon. Bon was not a religion in its own right, but the sum of all the indigenous beliefs, cults of local gods, popular rites, etc., that were prevalent across Tibet

When Buddhism was introduced into Tibet in the seventh century under King Songtsen Gampo, it was apparently centered in the royal court and did not, at first, put down deep roots. Buddhism became a major presence in Tibet towards the end of the 8th century CE under King Trisong Detsen, who with the aid of Padmasambhava strengthened its position. But even after that “first diffusion,” the new religion lost ground, and it was not until the “second diffusion” of Buddhism in the ninth and tenth centuries that it became firmly and finally established as the majority religion of Tibet.

Tibetan Buddhism inherited many of the traditions of late Indian Buddhism, including a strong emphasis on monasticism (Tibet was once home to the largest Buddhist monasteries in the world), a sophisticated scholastic philosophy, and elaborate forms of tantric practice. At the same time, Tibet continued its tradition of powerful popular cults, incorporating a wide variety of local deities into the already burgeoning Buddhist pantheon.

Tibetan Buddhism comprises four lineages. All trace themselves back to Buddha Shakyamuni in an unbroken lineage of enlightened masters and disciples. They are distinguished much more by lineage than by any major difference in doctrine or practice. The four lineages are Gelugpa, Sakyapa, Nyingmapa and Kagyupa.

- Nyingmapa: Founded by Padmasambhava, this is the oldest sect, noted in the West for the teachings of the “Tibetan Book of the Dead”. Nyingma can be translated as “ancient” and refers to the fact that they were, essentially, the first real school of Buddhism that wasn’t Indian in nature—it was Tibetan. It’s worth noting that in a heavily patriarchal society, Padmasambhava’s primary disciple was a woman known as Yeshe Tsogyal.

- Kagyupa: “Lineage of the (Buddha’s) Word”. This is an oral tradition which is very much concerned with the experiential dimension of meditation. Founded by Tilopa (988-1069) – named for his day job pounding sesame seeds (metaphorically grinding out the ego) – who was an ardent practitioner and became enlightened, developed a system of meditation known as “Mahamudra,” or “the great seal,” and passed these teachings about the nature of mind on to Naropa. Naropa had a great disciple, Marpa, who became known as the Great Translator. One of Tibet’s greatest yogi saints, Milarepa, was Marpa’s principle disciple, who then trained Gampopa, who then trained the first Karmapa who brought the teachings under the monastic umbrella.

- Sakyapa: “Sakya” is the Tibetan word for gray earth. The “Grey Earth” school represents the scholarly tradition. The Indian master Virupa is often considered a forefather to the Sakya lineage, who passed his teachings on to various Indian masters who passed them on to the Tibetan Drokmi Lotsawa Shakya Yeshe (992-1072 CE) when he traveled to India. Drokmi Lotsawa passed the lineage on to Khon Konchok Gyalpo and then, his son, Sakyapa Kunga Nyingpo, became his spiritual successor, which set a precedent for hereditary transmission going forward and is certainly unique in a religious tradition that normally emphasizes finding someone’s reincarnation and empowering them as successor.

- Gelugpa: (The Virtuous School or The Way of Virtue) was founded by Tsong Khapa Lobsang Drakpa (also called Je Rinpoche) (1357 – 1419). One of Tsongkhapa’s disciples became the first Dalai Lama and these reincarnated teachers have overseen the lineage ever since. Perhaps this tradition is the most renowned, as the head of this lineage is His Holiness the Dalai Lama of the present days.

Special features of Tibetan Buddhism:

– The Lama. Unique to Tibetan Buddhism is the institution of the tulku (incarnate lama). Tibetan Buddhists believe that compassionate teachers are reborn again and again. In each lifetime, they are identified when they are children and invested with the office and prestige of their previous rebirths. A living Lama is viewed as a teacher, and this status is often given to a senior member of a monastic community – a monk or a nun – but lay people and married people can also be Lamas. As well as being learned in Buddhist texts and philosophy, Lamas often have particular skills in ritual. There are two important kinds of Lamas:

– Dalai Lama. Dalai is a Mongol word meaning ocean and refers to the depth of the Dalai Lama’s wisdom. The first Dalai Lama to bear the title was the 3rd Dalai Lama, Sonam Gyatso. (The two previous incarnations were named “Dalai Lama” after their deaths.) The present (2010) Dalai Lama (the Fourteenth) Tenzin Gyatso, was born in Amdo, Tibet in 1935 and he is living in exile, in India, since he fled Chinese occupation of his country in 1959.

– The Karmapa Lama. Karmapa means “one who performs the activity of a Buddha”. The current incarnation (2002) is the 17th Karmapa. Two individuals have been declared the 17th Karmapa; Orgyen Trinley Dorje is generally and officially recognized as the official 17th Karmapa, however, a rival Buddhist group gives the allegiance to Trinlay Thaye Dorje.

– The relationship between life and death. Tibetan Buddhism emphasizes awareness of death and impermanence, this leading towards a holistic understanding and acceptance of death as an inevitable part of the life journey. Tibetan Buddhists use visualization meditations and other exercises to imagine death and prepare for the Bardo.

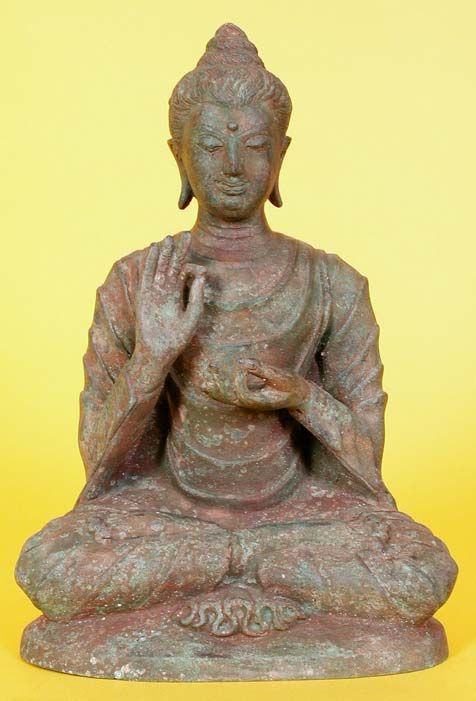

– The rituals and initiations. Rituals and simple spiritual practices such as mantras are popular with lay Tibetan Buddhists. They include prostrations, making offerings to statues of Buddhas or bodhisattvas, attending public teachings and ceremonies. Tibetan ceremonies are often noisy and visually striking, with brass instruments, cymbals and gongs, and musical and impressive chanting by formally dressed monks. It takes place in strikingly designed temples and monasteries.

– The rich visual symbolism. Supernatural beings are prominent in Tibetan Buddhism. Buddhas and bodhisattvas abound, also the gods and spirits taken from earlier Tibetan religions. Bodhisattvas are portrayed as both benevolent godlike figures and wrathful deities.

– Many advanced rituals. These are only possible for those who have reached a sophisticated understanding of spiritual practice. These include elaborate visualizations and demanding meditations. It’s said that senior Tibetan yoga adepts can achieve much greater control over the body than other human beings, and are able to control their body temperature, heart rate, and other normally automatic functions.

Photo credit: tibettravelorgblog