Buddha taught there are five types of factors at work in the cosmos that cause things to happen, called the Five Niyamas. The ‘five niyamas’ are the five kinds of laws which describe the arising and ceasing of conditioned phenomena comprehended within the principle of conditionality. Since natural laws as such are human productions of thought, there being five kinds of law is simply a convention.

The Sanskrit niyama is derived from the verbal root Öyam, ‘hold’, and etymologically means ‘holding-back’. It can mean an ethical ‘restraint’; niyama as the second of the eight limbs of aṣtāṅga-yoga refers to five ‘observances’. The Pali niyama is used in this way in the Milindapañha. More importantly, however, the Sanskrit word also means ‘necessity’.

The five Niyamas are:

Utu Niyama (“time, season”) seasonal changes and climate, law of non-living matter

Utu Niyama is the physical inorganic order, is the natural law of non-living matter. This natural law orders the change of seasons and phenomena related to climate and the weather. It explains the nature of heat and fire, soil and gasses, water and wind. Most natural disasters such as floods and earthquakes would be governed by Utu Niyama.

Put into modern terms, Utu Niyama would correlate with what we think of as physics, chemistry, geology, and several sciences of inorganic phenomena. The most important point to understand about Utu Niyama is that the matter it governs is not part of the law of karma and is not overridden by karma. So, from a Buddhist perspective, natural disasters such as earthquakes are not caused by karma.

Bija Niyama (“seed”) laws of heredity, “the constraint of the seasons”

Bija Niyama is the physical organic order, the law of living matter, what we would think of as biology. The Pali word bija means “seed,” and so Bija Niyama governs the nature of germs and seeds and the attributes of sprouts, leaves, flowers, fruits, and plant life generally.

The scientific theory of cells and genes and the physical similarity of twins may be ascribed to this order. Some modern scholars suggest that laws of genetics that apply to all life, plant and animal, would come under the heading of Bija Niyama.

Kamma Niyama (“action”) consequences of one’s actions, “the constraint of kamma”

Kamma, or karma in Sanskrit, is the law of moral causation. All of our volitional thoughts, words and deeds create an energy that brings about effects, and that process is called karma.

The important point is that Kamma Niyama is a kind of natural law, like gravity, that operates without having to be directed by a divine intelligence. In Buddhism, karma is not a cosmic criminal justice system, and no supernatural force or God is directing it to reward the good and punish the wicked.

Karma is, rather, a natural tendency for skillful (kushala) actions to create beneficial effects, and unskillful (akushala) actions to create harmful or painful effects. This constraint is said to be epitomised by Dhammapada, verse 127, which explains that the consequences of actions are inescapable.

Dhamma Niyama (“law”) nature’s tendency to perfect, “the constraint of dhammas”

The Pali word dhamma, or dharma in Sanskrit, has several meanings. It often is used to refer to the teachings of the Buddha. But it also is used to mean something like “manifestation of reality” or the nature of existence.

One way to think of Dhamma Niyama is as natural spiritual law. The doctrines of anatta (no self) and shunyata (emptiness) and the marks of existence, for example, would be part of Dhamma Niyama.

Citta Niyama (“mind”) will of mind, “the constraint of mind”

Citta, sometimes spelled chitta, means “mind,” “heart,” or “state of consciousness.” Citta Niyama is the law of mental activity — something like psychology. It concerns consciousness, thoughts, and perceptions.

We tend to think of our minds as “us,” or as the pilot directing us through our lives. But in Buddhism, mental activities are phenomena that arise from causes and conditions, like other phenomena.

In the teachings of the Five Skandhas, mind is a kind of sense organ, and thoughts are sense objects, in the same way the nose is a sense organ and smells are its objects.

***

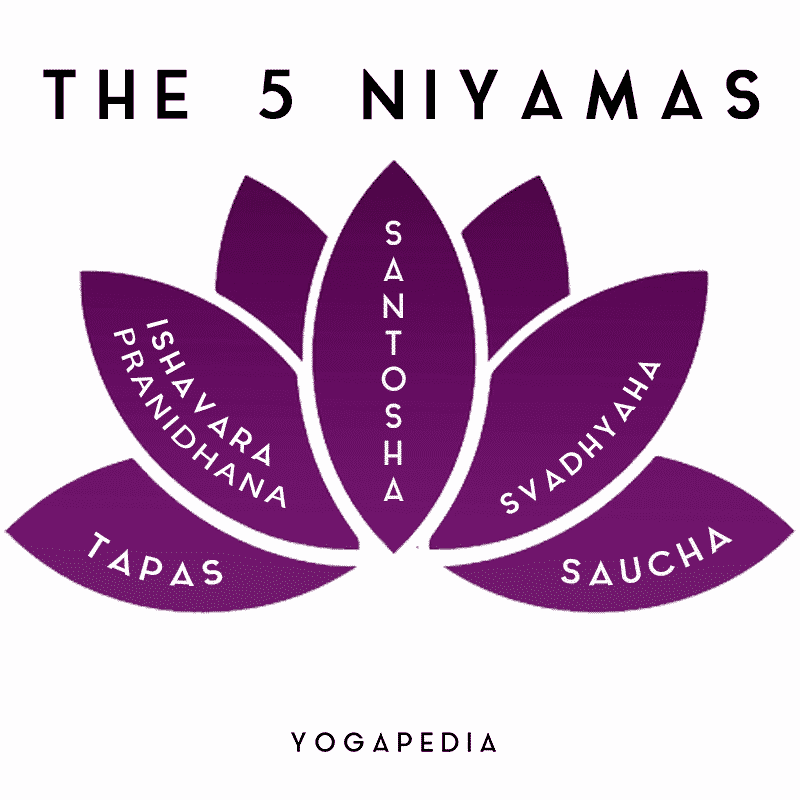

In Patanjali’s Yoga Sutras, the Niyamas are the second limb of the eight limbs of Yoga. Sadhana Pada Verse 32 lists the niyamas as:

– Śauca: purity, clearness of mind, speech and body

– Santoṣa: contentment, acceptance of others and of one’s circumstances as they are, optimism for self

– Tapas: austerity, self-discipline,[9] persistent meditation, perseverance

– Svādhyāya: study of self, self-reflection, introspection of self’s thoughts, speeches and actions

– Īśvarapraṇidhāna: contemplation of the Ishvara (God/Supreme Being, Brahman, True Self, Unchanging Reality)

***

The doctrine of five niyamas, or “orders of nature,” was introduced to Westerners by Mrs. Rhys Davids in her Buddhism of 1912. She writes that the list derives from Buddhaghosa’s commentaries, and that it synthesizes information from the pitakas regarding cosmic order. Several Buddhist writers have taken up her exposition to present the Buddha’s teaching, including that of karma, as compatible with modern science. However, a close reading of the sources for the five niyamas shows that they do not mean what Mrs. Rhys Davids says they mean. In their historical context they merely constitute a list of five ways in which things necessarily happen. Nevertheless, the value of her work is that she succeeded in presenting the Buddhist doctrine of dependent arising (paticca-samuppada) as equivalent to Western scientific explanations of events. In conclusion, Western Buddhism, in need of a worked-out presentation of paticca-samuppada, embraced her interpretation of the five niyamas despite its inaccuracies. (Divan Thomas Johnes)

Photo credit : slideshare