Eihei Dogen, also known as Joyo Daishi or Kigen Dogen (19 Jan. 1200, Kyoto, Japan—22 Sept. 1253, Kyoto), was born into a family of the court nobility. At the age of seven, Dogen lost his mother – who at her death earnestly asked him to become a monastic to seek the truth of Buddhism. We are told that in the midst of profound grief, Dogen experienced the impermanence of all things as he watched the incense smoke ascending at his mother’s funeral service. This left an indelible impression upon the young Dogen. (Later, he would emphasize time and again the intimate relationship between the desire for enlightenment and the awareness of impermanence. His way of life would not be a sentimental flight from, but a compassionate understanding of, the intolerable reality of existence.)

The orphaned boy was adopted by an uncle who was a powerful, highly placed adviser of the emperor of Japan. Young Dogen received a good education, which included study of important Buddhist texts. Dogen read the eight volume Abhidharma-kosa, an advanced work of Buddhist philosophy, when he was 9.

When he was 12 or 13 Dogen left his uncle’s house and went to the Tendai Center on Mount Hiei, where another uncle was serving as a priest. This uncle arranged for Dogen to be admitted to Enryaku-ji, a temple of the Tendai school, where, at age 13, Dogen received monk ordination and studied without, however, fully satisfying his spiritual aspirations. (Dogen was troubled by one particular question: if all human beings are born with Buddha Nature, why is it so difficult to realize it?) Disappointed, he sought for the answer elsewhere, so he went and studied with Eisai, a Rinzai master, who told him it was a delusion to think in such dualistic terms as Buddha Nature. With this answer Dogen experienced Satori. After Eisai’s death, Dogen continued to practice under Myozen, Eisai’s successor. After training for nine years, in 1223, Dogen (accompanied by Myozen) made the difficult journey to China, where he studied koans for two years, then – after Myozen’s death – he went to study under Master Tendo Nyojo (Ju-Tsing) in the Soto Zen lineage.

(Nyojo was practicing a different kind of Chan, just sitting – shikantaza – and Dogen took it to the extremes. The story goes that, one day, Master Nyojo was scolding another monk for sleeping during the period of sitting practice, saying, “The practice of Zazen (Sitting Meditation) is the dropping away of body and mind. What do you think dozing will accomplish?” Upon hearing these words, Dogen became fully Enlightened. He suddenly understood that Zazen is not just sitting still, but it is the “I” opening up to its own Reality. At that time he was 26 years old. He trained himself after enlightenment for two more years, and in the spring of 1228 he recieved the transmission of the Dharma from Nyojo. But years later, when Dogen returned to Japan, he said, “I have come back empty-handed. I have realized only that the eyes are horizontal and the nose is vertical.”)

Dogen returned to Kennin-ji and taught there for three years. However, by this time his approach to Buddhism was radically different from the Tendai orthodoxy that dominated Kyoto, and to avoid political conflict he left Kyoto for an abandoned temple in Uji. Eventually he would establish the temple Kosho-horin-ji in Uji. Dogen again ignored orthodoxy by taking students from all social classes and walks of life, including women.

But as Dogen’s reputation grew, so did the criticism against him. In 1243 he accepted an offer of land from an aristocratic lay student, Lord Yoshishige Hatano. The land was in remote Echizen Province on the Sea of Japan, and here Dogen established Eihei-ji, today one of the two head temples of Soto Zen in Japan. He spent his last years at Eihei-ji Temple, (The Temple of Eternal Peace) which he had founded on a hill – in present-day Fukui. In 1252, Dogen became ill, he named his dharma heir Koun Ejo the abbott of Eihei-ji, and traveled to Kyoto seeking help for his illness. He died in Kyoto in 1253.

Dogen taught a way of sitting called Shikantaza, “shikan” means nothing but, “ta” means to hit, “za” means to sit.

Shikantaza has remained the basis of Soto Zen up to the present. Dogen stated that the act of sitting itself is the actualization of Buddha Nature. The meditation does not strive for Satori, but has faith on the master (Buddha) and teachings (Dharma), and trusts that realization will come as a result of sitting practice.

Initially Dogen gave the meditation instructions in Fukanzazengi, “General Teachings for the Promotion of Zazen”, one of his first writings (1227). He wrote a number of other instructive works as well. His chief work, Shōbōgenzō (1231–53; “Treasury of the True Dharma Eye”), containing 95 chapters and written over a period of more than 20 years, consists of his elaboration of Buddhist principles. Instead of writing in classical Chinese, so popular in those days, Dogen used Japanese so that every one will be able to read it. His large body of writings are noted for their philosophical depths and evocative, poetic quality.

Dogen Zenji is considered to be the founder of The Soto Zen School.

To study the Way is to study the Self. To study the Self is to forget the self. To forget the self is to be enlightened by all things of the universe. To be enlightened by all things of the universe is to cast off the body and mind of the self as well as those of others. Even the traces of enlightenment are wiped out, and life with traceless enlightenment goes on forever and ever.

***

When you contemplate impermanence genuinely, the ordinary selfish mind does not arise, and you do not seek fame or fortune because you realize that nothing prevents the swift flow of time. You must practice the Way as though you were trying to keep your head from being consumed by fire…. If you hear the flattering call of the god Kimnara or the Kalavinka bird, regard them as merely the breeze blowing in your ears. Even though you see the beautiful face of Mao-ch’ing or Hsi-shih, consider that they are the morning dew obstructing your vision.

***

Firewood becomes ash; it can never go back to being firewood. Still, we shouldn’t imagine ash is its future and firewood is its past. We should recognize that firewood takes its place in the Universe as firewood, and has its past moment and its future moment. And though we can say firewood has both past and future, the past moment and the future moment are cut off. Likewise, ash takes its place in the Universe as ash, and has its past moment and its future moment. And just as firewood can never again be firewood after becoming ash, human beings cannot live again after their death. So it’s our way in Buddhism not to say life turns into death. This is why we speak of “no appearance.” And in the same vein, Gautama Buddha taught that death does not turn into life. This is why we speak of “no disappearance.” Life is an instantaneous matter, and death is also an instantaneous matter. It is like winter and spring. We do not imagine that winter becomes spring, and we do not say that spring becomes summer.

***

Treading along in this dreamlike, illusory realm,

Without looking for the traces I may have left;

A cuckoo’s song beckons me to return home;

Hearing this, I tilt my head to see

Who has told me to turn back;

But do not ask me where I am going,

As I travel in this limitless world,

Where every step I take is my home.

***

If you want to travel the Way of Buddhas and Zen masters, then expect nothing, seek nothing, and grasp nothing.

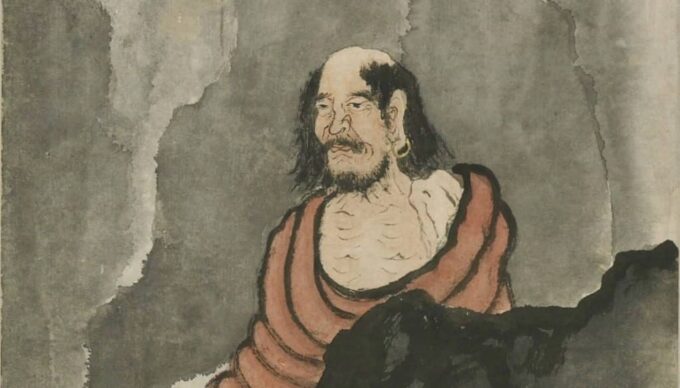

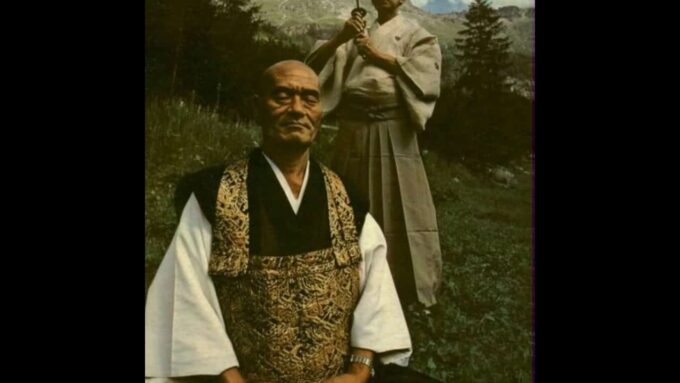

Picture source: chinese buddhist encyclopedia