by Roy Melvyn (Author) – excerpt of the book Zazen, Shikantaza and the Soto Tradition of Dogen

Some people think of zazen as a technique for reaching a state of “no thought.” Such an understanding of zazen assumes that a certain state of mind can be reached by manipulation, technique, or method. In the West, zazen is usually translated as “Zen meditation” or “sitting meditation.”

More and more, in contemporary usage, zazen is considered one of the many methods from Eastern spiritual traditions for attaining objectives such as mind/ body health, skillful social behavior, a peaceful mind, or the resolution of various problems in life. It is true that many meditation practices in the Buddhist tradition are helpful in achieving these objectives, and these may certainly be skillful uses of meditation tools. However, zazen, as understood by Dogen Zenji, is something different, and cannot be categorized as meditation in the sense described above. It would, therefore, be helpful to us to look at some of the differences between zazen and meditation.

Dogen (1200-1252) was the founder of the Soto Zen tradition and a meditation master par excellence. His Shobogenzo is one of the great masterpieces of the Buddhist doctrinal tradition. Contemporary scholars are finding much in this text to help them understand, not only a unique approach to Buddhadharma [the teaching of the Buddha] but also to zazen as practice. For Dogen, zazen is first and foremost a holistic body posture, not a state of mind. Dogen uses various terms to describe zazen, one of which is gotsu-za, which means “sitting immovable like a bold mountain.” A related term of great importance is kekka-fuza—“ full-lotus position”— which Dogen regards as the key to zazen. However, Dogen’s understanding of kekka-fuza is completely different from the yogic tradition of India, and this understanding sheds a great deal of light on how we should approach zazen. In most meditative traditions, practitioners start a certain method of meditation (such as counting breaths, visualizing sacred images, concentrating the mind on a certain thought or sensation, etc.) after getting comfortable sitting in full-lotus position.

In most meditative traditions, practitioners start a certain method of meditation (such as counting breaths, visualizing sacred images, concentrating the mind on a certain thought or sensation, etc.) after getting comfortable sitting in full-lotus position. In other words, it is kekka-fuza plus meditation. Kekka- fuza in such usage becomes a means for optimally conditioning the body and mind for mental exercises called “meditation,” but is not an objective in itself. The practice is structured dualistically, with a sitting body as a container and a meditating mind as the contents. And the emphasis is always on meditation as a mental exercise. In such a dualistic structure, the body sits while the mind does something else. For Dogen, on the other hand, the objective of zazen is just to sit in kekka-fuza correctly—there is absolutely nothing to add to it. It is kekka-fuza plus zero. Kodo Sawaki Roshi, the great Zen master of early 20th century Japan, said, “Just sit zazen, and that’s the end of it.”

In this understanding, zazen goes beyond mind/body dualism; both the body and the mind are simultaneously and completely used up just by the act of sitting in kekka-fuza. In the Samadhi King chapter of Shobogenzo, Dogen says, “Sit in kekka- fuza with the body, sit in kekka-fuza with the mind, sit in kekka-fuza of body-mind falling off.” Meditation practices which emphasize something psychological — thoughts, perceptions, feelings, visualizations, intentions, etc. — all direct our attention to cortical-cerebral functions, which I will loosely refer to as “Head.” Most meditation, as we conventionally understand it, is a work that focuses on the Head.

In Oriental medicine, we find the interesting idea that harmony among the internal organs is of greatest importance. All the issues associated with Head are something merely resulting from a lack of harmony among the internal organs, which are the real bases of our life. Because of our highly developed cortical-cerebral function, we tend to equate self-consciousness, the sense of “I,” with the Head—as if the Head is the main character in the play and the body is the servant following orders from the Head. However, from the point of view of Oriental medicine, this is not only a conceit of the Head but is a total misconception of life. Head is just a small part of the whole of life, and need not hold such a privileged position.

While most meditation tends to focus on the Head, zazen focuses more on the living holistic body-mind framework, allowing the Head to exist without giving it any pre-eminence. If the Head is over-functioning, it will give rise to a split and unbalanced life. But in the zazen posture, it learns to find its proper place and function within a unified mind-body field. Our living human body is not just a collection of bodily parts but is an organically integrated whole. It is designed in such a way that when one part of the body moves, however subtle the movement may be, it simultaneously causes the whole body to move in accordance with it. When we first learn how to do zazen, we cannot learn it as a whole or in a single stroke. Inevitably we initially dissect zazen into small pieces and then arrange them in a certain sequence: regulating the body, regulating the breath and regulating the mind.

In the Eihei-koroku Dogen wrote, “In our zazen, it is of primary importance to sit in the correct posture. Next, regulate the breath and calm down.” But after going through this preliminary stage, all instructions given as separate pieces in space and time must be integrated as a whole in the body-mind of the practitioner of zazen. When zazen becomes zazen, shikantaza is actualized. The “whole” of zazen must be integrated as “one” sitting. In other words, zazen must become “Zazen, Whole and One.”

How are this quality of being whole and one manifest in the sitting posture of zazen? When zazen is deeply integrated, the practitioner does not feel that each part of her/his body is separate from the others and is independently doing its job here and there in the body. The practitioner is not engaged in doing many different things in different places in the body by following the various instructions on how to regulate the body. In reality, he is doing only one thing to continuously aim at the correct sitting posture with the whole body. So in the actual experience of the practitioner, there is only a simple and harmoniously integrated sitting posture. S/he feels the cross-legged posture, the cosmic mudra, the half-opened eyes, etc., as local manifestations of the sitting posture being whole and one. While each part of the body is functioning in its own unique way, as a whole body they are fully integrated into the state of being one.

It is experienced as if all boundaries or divisions among the bodily parts have vanished, and all parts are embraced by and melted into one complete gesture of flesh and bone. We sometimes feel during zazen that our hands or legs have vanished or gone away. The term “shikantaza” might be best understood in terms of posture and gravity. All things on the ground are always pulled toward the center of the earth by gravity. Within this field of gravity, every form of life has survived by harmonizing itself with gravity in various ways.

We human beings attained upright posture, standing with the central axis of the body vertically, after a long evolutionary process. The upright posture is “anti-gravitational,” insofar as it cannot exist without uniquely human intentions and volitions that operate subliminally to keep the body upright. When we are sick or fatigued, we find it difficult to maintain the upright posture and lie down. In such situations, the intention to stand upright is not operational.

Although the vertical posture is anti-gravitational from one perspective, it can be properly aligned to be “pro-gravitational,” i.e. to follow gravity. When the body is tilted, certain muscles will become tense in order to maintain the upright posture; but if various parts of the body are integrated correctly along a vertical line, the weight is supported by the skeletal frame and unnecessary tension in the muscles is released. The whole body then submits to the direction of gravity. The subtlety of the sitting posture seems to lie in the fact that “anti-gravitational” and “pro- gravitational” states, which may seem contradictory at first glance, coexist quite naturally. Our relationship to gravity in shikantaza is neither an anti-gravitational way of fighting with gravity through tense muscles and a stiff body, nor a pro-gravitational way of being defeated by gravity with flaccid muscles and a limp body.

In shikantaza, while the body sits immovably like a mountain, the internal body is released, unwound and relaxed in every corner. Like an “egg balanced on end,” the outer structure remains strong and firm while the inside is fluid, calm, and at ease. Except for minimally necessary muscles, everything is quietly at rest. The more relaxed the muscles, the more sensible one can be, and the relationship with gravity will be adjusted more and more minutely. The more the muscles are allowed to relax, the more precise awareness becomes —and shikantaza gets deepened infinitely. I often find that people think of zazen as a solution to personal sufferings and problems or the cultivation of an individual. But a different perspective on zazen is provided by Kodo Sawaki Roshi’s words, “Zazen is to tune into the universe.”

The posture of zazen is connecting us to the whole universe. As Shigeo Michi, a well-known anatomist of the last century, puts it, “Since zazen is the posture in which a human being does nothing for the sake of a human being, the human being is freed from being a human being and becomes a Buddha.” (Songs of Life—Paeans to Zazen by Daiji Kobayashi). Michi also asks us to make a distinction between the “Head” and the “Heart,” saying how in zazen our internal “heart functions” reveal themselves quite vividly. The Head that I have been talking about may correspond to the technical Buddhist term “bonpu” which means ordinary human being. A bonpu is a non-Buddha, a person who is not yet enlightened and who is caught up in all sorts of ignorance, foolishness, and suffering.

When we engage in zazen wholeheartedly, instead of keeping it as an idea, we should never fail to understand that zazen practice is, in a sense, negation or giving up our bonpu-ness. In other words, in zazen we move from the Head to the Heart and into our Buddha- nature. If we fail to take this point seriously, we ruin ourselves by pandering to our own bonpu-ness; we get slack, adjust zazen to fit our bonpu-ness, and ruin zazen itself. Dogen Zenji said, “[when you sit zazen] do not think of either good or evil. Do not be concerned with right or wrong. Put aside the operation of your intellect, volition and consciousness. Stop considering things with your memory, imagination, or reflection.”

Following this advice, we are free, for the time being, to set aside our highly developed intellectual faculties. We simply let go of our ability to conceptualize. In zazen, we do not intentionally think about anything. This does not mean that we ought to fall asleep. On the contrary, our consciousness should always be clear and awake. While we sit in zazen posture all our human abilities, acquired through eons of evolution, are temporarily renounced or suspended. Since these capacities—moving, speaking, grasping, thinking—are the ones which human beings value the most, we might accurately say that “entering zazen is going out of the business of being a human being” or that in zazen “no human being business gets done.”

What is the significance of giving up all these hard-won human abilities while we sit in zazen? I believe it is that we have the opportunity to “seal up our bonpu-ness.” In other words, when sitting in zazen we unconditionally surrender our human ignorance. In effect, we are saying “I will not use these human capacities for my confused, self-centered purposes. By adopting zazen posture, my hands, legs, lips and mind are all sealed. They are just as they are. I can create no karma with any of them.” That is what “sealing up of bonpu-ness” in zazen means. When we use our sophisticated human capacities in our everyday lives we always use them for our deluded, self-centered purposes, our “bonpu” interests.

All our actions are based on our desires, our likes and dislikes. The reason we decide to go here or there, why we manipulate various objects, why we talk about various subjects, have this or that idea or opinion, is determined only by our inclination to satisfy our own selfish interests. This is how we are. It is a habit deeply ingrained in every bonpu human being. If we do nothing about this habit, we will continue to use all our wonderful human powers ignorantly and selfishly, and bury our- selves deeper and deeper in delusion. If on the other hand we correctly practice zazen, our human abilities will never be used for bonpu interests. In this way, this tendency will be halted, at least for a time. This is what I call “sealing up bonpu-ness.” Our bonpu-ness still exists, but it is completely sealed up.

Dogen Zenji described zazen in the Ben-dowa (On Following the Way) as a condition in which we are able “to display the Buddha seal at our three karma gates— body, speech and mind—and sit upright in this samadhi.” What he means is that there should be absolutely no sign of bonpu activity anywhere in the body, speech or mind; all that is there is the mark of the Buddha. The body does not move in zazen posture. The mouth is closed and does not speak. The mind does not seek to become Buddha, but instead stops the mental activities of thinking, willing, and consciousness.

By removing all signs of bonpu from our legs, hands, mouth and mind (which ordinarily act only on behalf of our deluded human interests), by putting the Buddha seal on them, we place them in the service of our Buddha nature. In other words, when our bonpu body-mind acts as a Buddha, it is transformed into the body-mind of a Buddha. We should be very careful about the fact that when we talk about “sealing up our deluded human nature” this “deluded human nature” we are talking about is not something which exists as a fixed entity, as either a subject or an object, from its own side. It is simply our perceived condition. We cannot just deny it and get rid of it. The fact of the matter is that when we sit zazen as just zazen, without intentionally intending to deny anything, our deluded human nature gets sealed up by the emergence of our Buddha nature at all three gates of karma, i.e. at the level of our body, speech and mind.

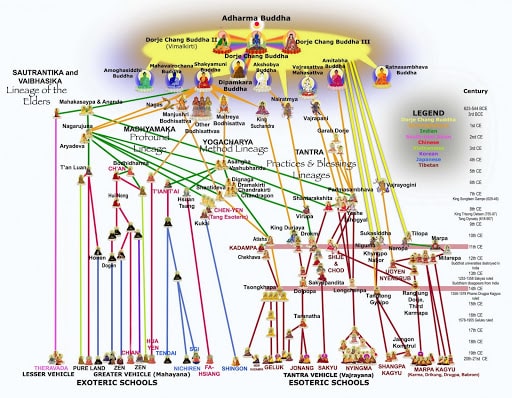

As a result, our deluded human nature is automatically renounced. All the foregoing explanations—of renunciation, of sealing up, of deluded human nature—are just words. These explanations are based on a particular, limited point of view, looking at zazen from outside. Certainly, it is true that zazen offers us the opportunities I have been describing. However, when we practice zazen we should be sure not to concern ourselves with “deluded human nature,” “renunciation,” or any such idea. All that is important for us is to practice zazen, here and now, as pure, uncontaminated zazen. The end result of such uncontaminated zazen is Silent illumination, which comes from the integrated practice of shamatha (calming the mind) and vipassana (insightful contemplation) called yuganaddha (union), and was the hallmark of the Caodong school of Ch’an. It, therefore, means one is practicing with both a calm mind and “questioning observation.”