by Daitsu Tom Wright*

*extract of the book Opening the Hand of Thought by Kōshō Uchiyama

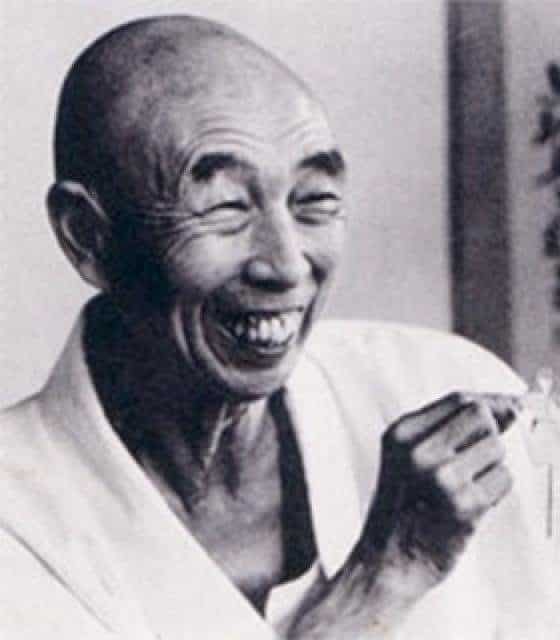

Kōshō Uchiyama

One of the most challenging teachings of Buddhism and of Kōshō Uchiyama Roshi’s teaching in particular centers around the nature of self and the meaning of the term jiko.

“Self” is only a rough translation for jiko, though, because “self” has cultural, psychological, and philosophical meanings for English speakers that inevitably differ from the terrain the word jiko covers in Japanese.

And even within Japanese, jiko has Buddhist meanings that differ from ordinary usage. Jiko is defined in Nakamura Gen’s Larger Dictionary of Buddhist Terms (Bukkyōgo Daijiten) as both the individual self and “original self,” which is the self that is born with or inherently has a buddha nature. All sentient beings possess the seed of awakened or awakening being, so original self is universal.

Many Buddhist and Zen texts, like the Blue Cliff Record, have expressions like iiko ichidan no daiji, that is, clarifying “self” is of vital significance. A basic characteristic of existence that is of particular relevance here is that all phenomena (dharmas) are without an independent self.

This is one of the three, or sometimes four, characteristics of existence that are a basic teaching of Buddhism and are discussed in this book. The translation of Buddhist terms as “self” leads to a big problem: if there is no self, then why is it necessary to clarify what the self is? You may think it best to stick to English words, but if you do not know their origins it will be hard to make sense of the different meanings mixed together in the one seemingly simple word “self.”

What has traditionally been translated as “self” in the expression “all dharmas are without an independent self” is the Sanskrit word atman. In Japanese atman is translated as ga, a substantive, clinging, avaricious spirit or soul. This is not jiko.

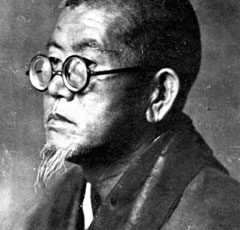

Kodo Sawaki and Kosho Uchiyama

The first time I remember coming across the term jiko was when a senior monk at Antaiji pointed it out to me in the chapter entitled Genjō Kōan in Eihei Dōgen’s Shōbōgenzō. At the time, I was reading through an English translation and was curious about what Japanese expression had been used. The passage turned out to be one of the most famous in the entire Shōbōgenzō.

“To practice and learn about the Buddha Way is to practice and learn about jiko. To practice and learn about jiko means to forget jiko. Forgetting about jiko, one is affirmed by all things, all phenomena (all dharmas). To be affirmed by all things means to be made to let go of all concepts and artificial divisions of one’s body and mind, as well as the body and mind of others, by those very things that affirm us.”

It is not easy to understand the deeper layers of this passage without giving a great deal of thought to how the word “self” is being used. For example, in the opening line, where Dōgen equates the study and practice of the Buddha Way with the study and practice of jiko, jiko is being used in its broad, universal sense. In the next line, however, it is different. Although the line appears paradoxical, that learning about jiko is forgetting about jiko, what Dōgen is saying is that in learning about jiko in the broadest sense, that is, as our universal identity, we have to forget or let go of all the narrow ideas we might have about who we are. To illustrate this point, Uchiyama Roshi used to bring up many concrete examples.

On a crowded train, and in Japan that is a supremely concrete event, forgetting or not clinging to thoughts of who we are in terms of our status, age, or gender means to get up and give our seat to someone who looks much more tired than we are, without thinking about doing a good deed or being well thought of. The same spirit comes up in not clinging to a feeling of frustration when we have to cook for the group and won’t be able to sit with everyone else. Or not getting upset because we have been asked to clean the toilet instead of our teacher’s room, where no one will see what good work we are doing. The examples are limitless in all our lives.

As the years went by and Uchiyama Roshi asked either Shohaku Okumura or me how we were translating the term, he began to feel that perhaps it would be best not to translate it at all and just use the term jiko, allowing readers to taste it for themselves. For example, Dōgen coined the phrase jin-issai-jiko. The first character jin means complete or exhaustive, while issai denotes everything, all, or all inclusive.

Jin and issai are attached to jiko to make it more comprehensive. Setting these characters in front of jiko, we come up with something like complete-all- inclusive-self; accurate, but hardly a usable English expression. Kōdō Sawaki Roshi had an enigmatic expression jiko ga jiko wo jiko suru, where the word “self” is being used as the subject, the verb, and the object. It is almost untranslatable; perhaps “the self makes the self out of the self.” Uchiyama Roshi had a similar expression, jiko giri no jiko, self that is wholly self. I believe Sawaki and Uchiyama coined their modern-day expressions as interpretations of Dōgen’s jin-issai-jiko.

Uchiyama and Sawaki

I have translated jiko as universal self or whole self, or more recently as universal identity. This is the same as buddhata, or awakened being, which I mentioned above. But this sounds quite abstract, when what we most need is to understand just what this means in the context of our daily lives. It is precisely this, Zen in our daily lives, that Uchiyama Roshi stressed more than anything else. After all, when asked to introduce ourselves or identify ourselves on meeting someone for the first time, we will most likely be thought weird if we reply, “Hi, I’m the Entire Universe, nice to meet you.” Jiko is used in everyday Japanese to identify ourselves in an individual sense, not as the universe.

In modern Japanese jiko is used in terms like jiko chushin, or jikoshugi, meaning egocentrism or self- centeredness. In this case, the term is being used in a dualistic sense of oneself as opposed to another, and it implies a view of the individual that emphasizes our self-importance and degrades the importance of those around us.

Although he had studied philosophy, not psychology, at Waseda University, Uchiyama often referred jokingly to himself as a psychologist’s psychologist. An endless parade of visitors came to see him—business executives from around the country, medical doctors, and psychologists, too. They came for counseling about the problems in their personal, self-centered lives, and he received them all. He also saw that some people’s psychological difficulties might be alleviated by sitting in the zazen posture to get some composure. If doctors or psychologists felt their patients had greatly benefited from the incorporation of zazen into their therapies, all the better.

At the same time, he would point out to me that such uses of zazen should be understood as being examples of bonpu zen, that is, utilitarian Zen, or Zen for the sake of bettering or improving your condition or circumstances. If such Zen can be helpful to people, he never criticized its use, but he did point out that utilitarian Zen should not be equated with doing zazen without setting any preconditions or objectives. In other words, Roshi made a distinction between practicing zazen unconditionally, with an attitude of letting go of all thoughts of how zazen could benefit “me,” and zazen done for utilitarian purposes.

Jiko in Buddhism and in Dōgen’s and Uchiyama’s teachings is not about utility and self-improvement. Rather it has to do with seeing one’s life from the broadest perspective and then functioning in a way that enables that perspective to manifest most fully through one’s day-to-day activities.

*Daitsu Tom Wright was ordained by Uchiyama Roshi in 1974 and is a professor of English at Ryukoku University in Kyoto, Japan.

Daitsu Tom Wright