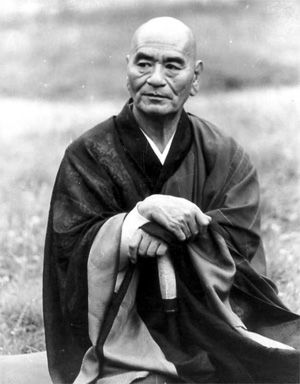

Taisen Deshimaru (Yasuo was his given first name) was born in on November 20, 1914, near the town of Saga, on the isle of Kyushu. His mother was a fervent Buddhist, a devout follower of the Jodo Shinshu sect of Buddhism, and his father a businessman (his father ran the local fisherman’s trade union). The polarity of their worldviews made a mark on the boy, who from a very young age considered it his destiny to resolve the contradiction between the spiritual and the material world.

Deshimaru was also raised by his grandfather, a former Samurai before the Meiji Revolution. Deshimaru had a happy childhood, but he was nonetheless tormented by the ephemeral world of birth and death. In his youth, having not much interest in his mother’s Nembutsu Buddhism, he turned to Christianity and studied it for a long while under a Protestant minister, before ultimately deciding that it was not for him. Dissatisfied with Christianity, he eventually returned to Buddhism. Consequently, he came into contact with the Rinzai teachings. Eventually becoming dissatisfied with Rinzai as well, and he subsequently left the organization.

As a youngster, Taisen Deshimaru was strongly influenced by the spirit of Bushido that was prevalent in Japan at that time, especially in the town of Saga – an important spiritual place for the samurai, and by the martial arts, as his grandfather thought him both Kendo and Judo.

Kodo Sawaki

In 1935, while studying Economics in Tokyo, unsatisfied by his life as a businessman, he began practicing Soto Zen with Kodo Sawaki Roshi, one of the great Zen masters of the twentieth century, who was godo (instructor of monks in the dojo) of Sojiji temple, one of the two main temples of the Soto School. Deshimaru met Kodo Sawaki when he was eighteen.

Arriving for the first time in the Master’s hermitage, he found Kodo Sawaki sitting erect on a cushion with his back to the door. Overcoming his initial awe – the Master was sitting in the perfect posture of the Buddha – he addressed the master. Kodo Sawaki did not reply, and Deshimaru was left standing awkwardly in the doorway. He repeated himself, and again there was no reply. Kodo Sawaki finally said: “I have been waiting impatiently for your visit.” The Master uttered these words without turning to his visitor, without the slightest movement, without even lifting his eyes. Deshimaru did gassho, and in that moment he became Kodo Sawaki’s disciple.

Deshimaru began sitting zazen with him two years later. He saw the master regularly while continuing his life as a businessman and, later, Deshimaru got married and became a father of three children.

Deshimaru repeatedly asked Sawaki for the monk ordination and was always refused. He was encouraged to simply continue zazen and to have an active layman’s life. Sawaki’s reluctance to settle down in a temple also made a strong impression on Deshimaru, who never lived a monastic life.

They remained together until Deshimaru began his period of service in the Japanese Army during World War II.

War

Deshimaru was being sent on a dangerous mission over enemy waters, and the Master knew this, and so he removed his old Rakusu (a material worn over the neck and breast, symbolic of a Kesa) and gave it to his disciple, along with his notebook containing the Shodoka. “Respect and have faith in what I have given you,” said the Master, “and you will have good karma.”

Deshimaru, whose job it was to direct a Japanese-controlled copper mine off Indonesia, shipped out in a convoy of freighters and destroyers. However, once they were beyond Japanese-controlled waters, submarines of the United States Navy made devastating attacks on the convoy, sinking one ship after the other. Deshimaru’s freighter was carrying a cargo of dynamite, and whenever a torpedo skirted the bow or the stern, crew members, beyond themselves with fear, plunged blindly overboard. The ship was in the hands of a capable captain, however, and so Deshimaru sat on the forecastle below the captain’s cockpit in the perfect full lotus. He sat, calmly and erect, on a case of dynamite. Forty days later Deshimaru’s unarmed freighter pulled into the Mekong and threw anchor. Of a convoy of fifty-one ships, his alone arrived at its destination. The freighter, incidentally, was called The Supreme Law of the Buddha.

Finding himself on the island of Bangka, off the coast of Sumatra, Deshimaru taught the practice of zazen to the Chinese, Indonesian and European inhabitants. However, saddened and depressed by the comportment of his own people (the Japanese Army of Occupation was indiscriminately torturing and executing large numbers of the local inhabitants), Deshimaru actively took up the Bangka people’s cause. Tagged as a resistance fighter against the Imperial Japanese Army, Deshimaru was thrown into prison. Despite malaria, the intense heat, the flies, the filth, the lack of food and water, and his scheduled execution, the man sat facing a wall in his cell, with his Master’s Rakusu about his neck.

Directly before the mass execution was to take place, word arrived from the highest military authorities in Japan, and Deshimaru, along with all those awaiting execution with him, was set free. (The Japanese Military Tribunal that convened after the war ordered the execution of all those responsible for the Bangka Affair).

Recovered from a life-and-death bout with malaria, Deshimaru again set sail, this time for the island of Billiton, where he was to direct a Dutch-captured copper mine. His ship had hardly set out when American fighter planes swept down on it. Their rockets scored direct hits, and Deshimaru, who was sitting on the bridge in Shikantaza, was hurled clear of the sinking ship and into the sea. Utterly alone, and without a life jacket-with nothing, in fact, except the old Rakusu and notebook on him-he remained afloat for a day and a night. Discovered eventually by a Japanese PT boat, Deshimaru was pulled to safety Though his clothes were torn and half gone, the Rakusu came out intact. And the Master’s notes, written in ink, were as fresh and clear as when they were first penned.

When the war was finally over, Deshimaru was taken prisoner by the Americans and incarcerated in a prisoner-of-war camp in Singapore. After many more months of hardship (corned beef rations being their sole luxury), Deshimaru, along with the other twenty thousand Japanese war prisoners in the same camp, was returned to his homeland.

Deshimaru rejoined his Master and remained by his side until the latter’s death fourteen years later. He received the monastic ordination shortly before the Master fell ill, and he received the Transmission (the Shiho) while Kodo Sawaki was on his deathbed. As material evidence, the Master gave his disciple the Kesa. So the Transmission and the Kesa, handed down from Buddha to Buddha and from Patriarch to Patriarch, were passed on from Master Kodo Sawaki to Master Taisen Deshimaru in the year 1965.

After burying Kodo Sawaki’s skull in the ground outside the Dojo, Deshimaru sat immobile in the perfect posture of the Buddha for forty-nine days. Then he left his homeland for the West.

From the time of Buddha to that of Bodhidharma, seven hundred years went by, from Bodhidharma to Dogen another seven hundred years; and from Dogen to Deshimaru seven hundred years.

When the war was finally over, Deshimaru rejoined his master and remained by his side until the latter’s death. He received the monastic ordination shortly before the master fell ill.

A month before he died, Sawaki summoned Deshimaru to his sick bed and said, “You must continue after me and transmit Bodhidharma’s teaching. Tomorrow I will get up to ordain you a monk.”

In 1965, while Kodo Sawaki was on his deathbed, Deshimaru received the transmission (the Shiho). The master also commissioned Deshimaru to go to the west “so that Buddhism may again flourish.”

After Kodo Sawaki’s death, in order to pay homage to his Master, Taisen Deshimaru sat in Zazen for forty-nine days.

Following directly in his Master’s footsteps, he devoted himself, body and mind, to the practice of Shikantaza.

France

Two years later, in 1967, invited by a group of French macrobiotics, Deshimaru entrusted the care of his family to his son, settled his business affairs, and took the Trans-Siberian rail to France, with no money, no knowledge of a single word of French, and no possessions other than his zafu, his kesa and his master’s kesa and notebooks. He was 53.

He lived in the back room of a health-food store, practicing zazen every day in the storage area, surviving by giving shiatsu massages and lectures on Zen Buddhism. He was not able to speak French and only knew very basic English.

As word spread that a real Zen master was living on the rue Pernety, people began sitting with him, and his reputation grew. More and more people came to practice. In 1972, he opened his first dojo in Paris’ 14th arrondissement and began giving ordinations and leading sesshins. There, he committed himself totally to the teaching of zazen and of the Zen tradition. It was the right moment, and his mission quickly made a big impression. Within a few years, he had done numerous talks, led sesshins, translated basic Zen texts, published written works, and, in 1970, he created the European Zen Association (and then International Zen Association). During the following years, with the help of his ever-growing number of students, he created more than one hundred Zen dojos in both Europe and in North America.

Deshimaru founded the temple La Gendronnière in 1979, the largest Zen temple outside Japan. The temple was officially recognized by Japanese Soto Zen authorities as the Head Temple of Europe.

He published his first book, True Zen (Vrai Zen) and began lecturing in France and other European countries.

In 1970, Deshimaru received dharma transmission from Master Yamada Reirin. In 1976, he became Kaikyosokan (head of Japanese Soto Zen for a particular country or continent) in Europe.

From then on, the scale of his missionary work got larger and larger, and, because of the increasing number of disciples, introducing and adapting the tradition and managing the whole association, required more and more work. He wanted to bring over other Japanese teachers to assist him, but he fell ill in 1981.

Death

In early 1982, Taisen Deshimaru was diagnosed with pancreatic cancer. He continued to practice with his disciples through the spring of that year. As he left for Japan to receive medical treatment, his last words were, “Please, continue Zazen.” Taisen Deshimaru Roshi died in Japan on April 30-th, 1982, after he had solidly established Zen practice in the West.

Work

Blessed with extraordinary energy, Taisen Deshimaru Roshi was animated by an unwavering faith in zazen practice, in the pure teachings of the buddhas and patriarchs, and in the importance of this practice and teaching for the coming civilization. He transmitted this faith to many of the disciples he had trained, some of whom he designated as future masters.

Taisen Deshimaru was the founder of Zen in Europe and thus firmly planted the living tradition of Zen in fresh soil. His teachings and multitude of books helped spread the influence of Zen in Europe and America, particularly of the Soto sect.

Taisen Deshimaru left his disciples with the essence of Zen, which had been transmitted from Master to disciple since the Buddha. His teaching was very humorous and simple, yet concrete and deeply rooted in daily life. Like Dogen Zenji and Kodo Sawaki before him, he insisted on the importance of shikantaza, and he encouraged his disciples to live without ego, self-interest, or desire for personal profit, and to follow the cosmic order “unconsciously, naturally and automatically”.

Because of his unique character, his uncompromising Zen practice, and his pioneering mission to spread Zen in Europe, Taisen Deshimaru is called, in his homeland of Japan, “The 20th Century Bodhidharma”. (Zen-Buddhism)

Taisen Deshimaru was one of the first Zen masters of the West. He established a retreat/monastery in France after deciding that French philosophy has numerous unrecognized Zen undercurrents. He basically sought to bridge the gap between Eastern and Western philosophy, and he did so wonderfully, speaking and writing in such a way that is both true to Zen and accessible to a layperson audience.

While in Europe, he learned how to make Oriental concepts understandable to the Western mind. In an interview, Deshimaru affirmed he chose France to teach because of its philosophical tradition; he cited Michel de Montaigne, René Descartes, Henri Bergson and Nicolas Malebranche as philosophers who understood Zen without even knowing it.

He pursued his mission with a prodigious, unflagging energy, always seeking to reconcile tradition and modernity, science and spirituality, East and West, and always returning to the essence of the teaching he received from his master. He had exceptional charisma, a great simplicity mixed with a sense of humor, which attracted not only disciples but also some of the most intriguing scientists, artists, philosophers and politicians of his time.

Deshimaru endured thorny relationships with the official Japanese Soto authorities (Sotoshu) and the major Zen schools in the United States. He was critical of the former for its formalism and the latter for its “mixture” of Soto and Rinzai Zen. While his contribution to the dissemination of Zen is acknowledged today in Japan, he remains unpopular, or at best unknown, in the United States.

“People may criticize me for many things,” he once said, “but they’ll never be able to say anything about zazen. Every morning and every evening I am with you in the dojo.”

Books

Za-Zen, the practice of the Zen

Sit: Zen Teachings of Master Taisen Deshimaru

The Ring of the Way: Testament of a Zen Master

Questions to a Zen Master

The Zen Way To Martial Arts

The Way of True Zen

The Voice of the Valley

Quotes

Religions remain what they are. Zen is meditation. Meditation is the foundation of every religion. People today feel an intense need to go back to the source of religious life, to the pure essence in the depths of themselves which they can discover only through actually experiencing it. They also need to be able to concentrate their minds in order to find the highest wisdom and freedom, which is spiritual in nature, in their efforts to deal with the influences of every description imposed upon them by their environment. Human wisdom alone is not enough, it is not complete. Only universal truth can provide the highest wisdom. Take away the word Zen and put Truth or Order of the Universe in its place.

If you are not happy here and now, you never will be.

“If the body is strong and the mind is weak, the body kills mind. And you become insane. If the mind is strong and the body weak, then mind kills the body. And you commit suicide.”

“In a sutra, it is written that if you want to have a second bowl of soup and at this moment you decide not to have it, then this will become a great fuse for all humanity. If you wish to change your tiny room for a big apartment and you do not, then this will become a great fuse for all humanity.”

“Imagination, images, are created by our own mind, by our consciousness. Our mind makes naraka (hell); it makes suffering. Each person is living in a world which he creates by his own proper consciousness. So, what is the ego?…. Each one of us thinks: “I am me,” I am like this or like that; and we understand this through going un, the five aggregates (sensation, perception, thought, activity, and consciousness). This is gyo and shiki-egoisticgyo and egoistic Shiki. But to understand unconsciously, objectively-this is history consciousness. And so at this moment, our egoistic desires can be sublimated to a higher level. This is the teaching of Zen. It is the highest wisdom for daily living.”

“If you have a glass full of liquid you can discourse forever on its qualities, discuss whether it is cold, warm, whether it is really and truly composed of H-2-O, or even mineral water, or sake. Meditation is Drinking it!”

“Nobody today is normal, everybody is a little bit crazy or unbalanced, people’s minds are running all the time. Their perceptions of the world are partial, incomplete. They are eaten alive by their egos. They think they see, but they are mistaken; all they do is project their madness, their world, upon the world. There is no clarity, no wisdom in that!”

True religion is not esoteric or mystical, it is not an exercise in well-being or gymnastics. True religion is the highest Way, the absolute Way: zazen. Zazen cannot be an imitation, a fake. Zazen does not allow lies. It is a difficult Way, but difficulty helps. Sometimes adversity can be beneficial. Without adversity, people go soft like the face of a cat in the corner of a hearth. Wild cats or dogs are stronger than pets because they are always subject to difficulties. Those who truly seek the Way should not hope that it will be easy. An easy path is not authentic.

Question: In your opinion, what are you? A master? A religious leader? A philosopher?

Taisen Deshimaru: Ha! Good question. I sometimes wonder myself. But what you are doing is limiting by categories. You can’t do that. Sometimes I am a philosopher, sometimes a religious person, sometimes a monk, sometimes an educator, sometimes a whiskey-drinker. A great historian can understand: it’s the disciples who decide. If great disciples arise, then you have great masters. I am a religious man. I concentrate completely on shikantaza. Until death. This is my only object. When I die, then here and now, only this: true Zen monk. Understand? (Zen-Road)

Text and Quotes: From Taisen Deshimaru, The Voice of the Valley.

Deshimaru Quotes: Wiki

Interview

mondo: mondo

Video (Fr): Taisen Deshimaru, A Zen Master in Europe

photo credit: Deshimaru