Camellia-petal

fell in silent dawn . . . spilling

A water-jewel

Haiku is a contemplative, unrhymed Japanese poem that attempts to chronicle the essence of a moment in which nature is linked to human life. It is one of the most important forms of traditional Japanese poetry. The modern form of haiku dates from the 1890s and is developed from earlier forms of poetry, hokku and haikai. Although there were many great Haiku poets, it is generally acknowledged that there were four great masters: Matsuo Basho, Yosa Buson, Kobayasshi Issa, and Masaoka Shiki.

Haiku is a Japanese art form born from Buddhism, Taoism, and Shintoism. It can be traced back to the seventeenth century in Japan, where it evolved from the two kinds of older poetry called renga and tanka. First known as hokku, haiku was only given its current name in the nineteenth century by a Japanese writer named Masaoka Shiki (1867–1902), who described the haiku as being “verbal sketching”—little works of art that capture something observed.

The haiku was expressed in the popular idiom, avoiding all literary sounding phrases. It is, by excellence, the poetry which celebrates the commonplace. A haiku is extremely short so that it is recited in one breath.

Gazing at the flowers

of the morning glory

I eat my breakfast.

In the traditional Japanese form, there were a number of set regulations that were to be followed by haiku practitioners. Each poem had to include four elements, chosen for their congruence with the larger subject of the poem: season, location (in a general sense), time of day (kigo), and the “atmosphere” which the poem is to suggest or elucidate.

Traditional Japanese poetry is based on combinations of lines of five and seven onji, a syllable-like pattern unit of a vowel or a consonant and vowel, originally arranged in vertical columns. The traditional Japanese haiku is written in seventeen syllables (broken down into patterns of 5-7-5) and has three short lines – with the second line typically longer than the other two. The length of a haiku (in any language), should be one breath long. The shortness of these poems is a reflection of Zen philosophy, which emphasizes being in the prezent moment.

Most Japanese haiku also have what are called “cutting words” or kireji which serves as a pause. The kireji is a special grammar word or verb ending that indicates the completion of a phrase or clause. In effect, the kireji is a sort of sounded, rather than merely written, punctuation. It indicates a pause, both rhythmically and grammatically. The haiku is also having a pivot in the middle of the poem. The pivot line should logically follow the first line and logically precede the last line. Technically, this means the haiku may hold two separate thoughts.

Unlike other poetry, haiku generally do not use metaphor or obscure imagery, nor reflect the feelings or inner life of the poet–at least in an explicit way. It is rather an expression of egolessness in which the poet turns outward to fully experience and capture the essence of being in a particular moment at a particular place. Therefore, the haikus are written in the present tense.

Lightening –

Heron’s cry

Stabs the darkness

Haiku is a form that is deceptively simple.

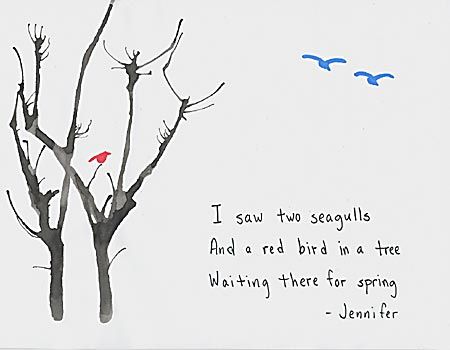

Haiku is a form that is deceptively simple. The simplicity of haiku is also what gives them the flexibility to be integrated into other related forms. For instance, haiku poets might also write haibun (prose essays that describe a situation). Sometimes the haiku is written out in calligraphy and a Japanese brush-painted image is used to illustrate it, this resultig in a haiga (a work of art that is meant to be hung on a wall).

A tradition among Zen monks is to write a last haiku when they know that they are about to pass out of this life. Some of these haiku have been collected into the book Japanese Death Poems by Yoel Hoffman.

It includes this poem by Gozan, written at the age of 71:

- The snow of yesterday

- That fell like cherry petals

- Is water once again.

A well-written haiku creates tension between contrasting elements such as movement and inactivity, change and continuance, time and timelessness, nature and humanity. Most haiku poems contain themes that are simple to understand but give the reader new insight into a well-known experience or situation. The aesthetic of haiku is not far removed from that of Sumi-e or No drama. The basic principle is the same: the most of the essence with the least possible means.

Haiku avoids first person accounts and disallows the use of similes or metaphors. While some haiku poets try to experience the feelings of natural objects, it is not usually their intent to give human attributes to inanimate objects, nor to personalize nature. But the haiku expresses deep feelings for nature, including human beings. This follows the traditional Japanese idea that man is part of the natural world, and should live in harmony with it.

Within the highly restrictive verse form of seventeen syllables, the haiku presents a precisely chosen objective slice of nature, and its earthiness is accessible to all who can read or hear it read; it carries out in poetry the ideals of Hui Neng, the Sixth Patriarch of Zen Buddhism, who said that every man has the same ability and opportunity to become enlightened regardless of education or status.

Photo credit: poeticchampionsdotcom