When Hyakujo delivered a certain series of sermons, an old man always followed the monks to the main hall and listened to him. When the monks left the hall, the old man would also leave.

One day, however, he remained behind, and Hyakujo asked him, “Who are you, standing here before me?” The old man replied. “I am not a human being. In the old days of Kashyapa Buddha, I was a head monk, living here on this mountain. One day a student asked me, ‘Does a man of enlightenment fall under the yoke of causation or not?’ I answered, ‘No, he does not.’ Since then I have been doomed to undergo five hundred rebirths as a fox. I beg you now to give the turning word to release me from my life as a fox. Tell me, does a man of enlightenment fall under the yoke of causation or not?” Hyakujo answered, “He does not ignore causation.”

No sooner had the old man heard these words than he was enlightened. Making his bows, he said, “I am emancipated from my life as a fox. I shall remain on this mountain. I have a favor to ask of you: would you please bury my body as that of a dead monk.”

Hyakujo had the director of the monks strike with the gavel and inform everyone that after the midday meal there would be a funeral service for a dead monk. The monks wondered at this, saying, “Everyone is in good health; nobody is in the sick ward. What does this mean?”

After the meal Hyakujo led the monks to the foot of a rock on the far side of the mountain and with his staff poked out the dead body of a fox and performed the ceremony of cremation. That evening he ascended the rostrum and told the monks the whole story.

Obaku thereupon asked him, “The old man gave the wrong answer and was doomed to be a fox for five hundred rebirths. Now, suppose he had given the right answer, what would have happened then?”

Hyakujo said, “You come here to me, and I will tell you.”

Obaku went up to Hyakujo and boxed his ears.

Hyakujo clapped his hands with a laugh and exclaimed, “I was thinking that the barbarian had a red beard, but now I see before me the red-bearded barbarian himself.”

Mumon’s Comment

Not falling under causation: how could this make the monk a fox?

Not ignoring causation: how could this make the old man emancipated?

If you come to understand this, you will realize how old Hyakujo would have enjoyed five hundred rebirths as a fox.

Mumon’s Verse

Not falling, not ignoring:

Two faces of one die.

Not ignoring, not falling:

A thousand errors, a million mistakes.

The meaning of the koan has been the object of intense debate within Zen due to its complexity and multitude of themes. Hakuin (1686–1769) regarded it as a nantō koan, one that is “difficult to pass through” but has the ability to facilitate “post-enlightenment cultivation” or “realization beyond realization” (shōtaichōyō). Other themes included in this case speak about causality (karma in Buddhism), the power of language, reincarnation, and the folklore elements (the fox).

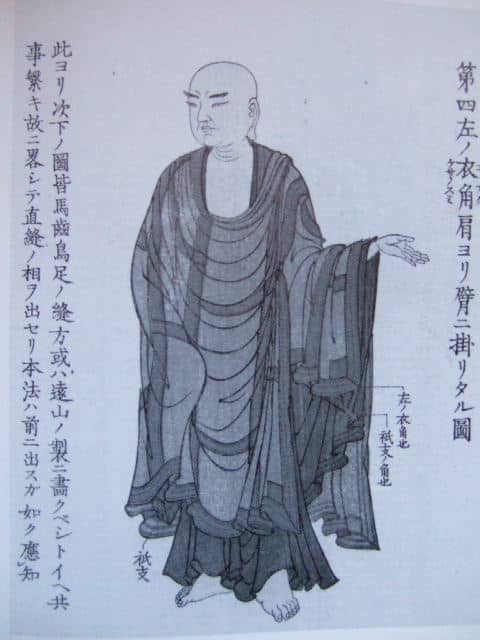

Hyakujo

Hyakujo Ekai (720–814 (Baizhang Huaihai) was a Chinese Zen master during the Tang Dynasty. He was a dharma heir of Mazu Daoyi. Baizhang’s students included Huangbo, Linji and Pu hua.

Kashyapa Buddha

Kashyapa Buddha was one of the Buddhas of this world prior to Shakyamuni, the Buddha of recent history and the Buddha who set the current Wheel of the Dharma rolling.

Fox

The fox in East Asia is looked upon as a kind of malevolent trickster. This koan is utilizing the Buddhist idea of rebirth as an animal, the East Asian idea of foxes as magical beings who can take on human form and who like to trick others. In ancient China, being reborn as a fox was no small matter as the fox was thought of as a disreputable animal and evidence of a very low birth. To live the life of a fox was thought to be a very miserable experience – clearly one to be avoided if possible.

But, some entertain the idea that maybe Hyakujo himself made up the whole story to make a point about how enlightened ones relate to causation (by being aware of it instead of denying it).

Obaku

Huang-po d. 850 Student of Pai-chang and teacher of Lin-chi (Rinzai). Huang-po had thirteen Dharma heirs and is a forefather of the Rinzai tradition.

Slapping the Master

Obaku went near Hyakujo and slapped the teacher’s face with this hand, for he knew this was the answer his teacher intended to give him.

Hyakujo didn’t want that the right answer is given as a matter of intellectual knowledge, he wanted a demonstration in concrete terms. He expected something that will show how all this talk of cause and effect, and awareness of it, can come to life in that moment.

A slap in the Zen context does not really mean abuse. A slap in Zen is meant to bring a person back to this moment. A slap is a concrete manifestation of the form.

Barbarian had a red beard

This may be a reference to Bodhidharma, who was said to have had a red-beard. Other translations of this story say “foreigner” instead of barbarian. If he was truly speaking about Bodhidharma, it means that when Obaku acted as he did, he displayed the very concrete awareness, insight, and ability to act naturally on that enlightened-awareness, actualizing the realization. Because not only the theoretical knowledge (based on the study of the sutras) is important, the point is to bring that knowledge into the actual awareness, in the ability to act concretely in the true spirit of the teachings through the zazen and other methods. In acting as he did, Hyakujo is saying that Obaku had brought Bodhidharma to life right then and there, by living his teachings.

Law of cause and effect

There are shallow and deep ways of understanding this law and how buddhahood relates to it. In effect, this koan raises the question of whether or not we can ever be free of the consequences of our actions. Is it always true that we are really subject to the law of karma – the law of cause and effect?

This koan presents 2 positions, and Mumon presents one more.

1 – The first answer is old monk’s one, who said that the law of Karma, or cause and effect, is so powerful that it governs everything in the universe, except the one who is Enlightened. Upon Enlightenment, the round of cause and effect loses its significance, just as Samsara, or the cycle of birth and death, ceases with Enlightenment. Therefore, when one is Enlightened, the law of Karma is not applicable.

Cause and effect, just like birth and death, lose their significance at the Enlightened level because at the level of basic nature there is no one to receive the effect of the Karma, whether it is good or bad. All that the Enlightened one does, says, or thinks is through free will, a manifestation of basic nature, and not the effect of past Karma.

For this answer he was doomed to appear as a fox until he gets the Dharma right.

2 – Hyakujo gave the second answer: “The enlightened man is one with the law of causation.” Other translations say: “The enlightened man is not blind to the law of causation.” So the point is there is no one to transcend and nothing to be transcended. The law of causation is one with us, and we can either be blind to it and act in ignorance, or we can be aware of it and work with the process, with the way things are, with the way we are. A Buddha is an “Awakened One” not one who has transcended to some other realm or reality.

For this answer he was slapped in the face.

3 – Mumon’s position is that these answers are presenting the limitations of the implied dualism in separating ourselves from cause and effect or separating causes and effects.

“There is no cause and effect in nature; nature has but an individual existence; nature simply is.”

In this koan we can see how past (Bodhidharma) becomes concretely present (a slap) and actualizes the goal of enlightenment (the future). Cause and effect have become one, because they are no longer a linear chronology of past cause leading to present effect, or present cause leading to future effect, but cause and effect both present in one action. Mumon slaps both of them, saying “a thousand errors, a million mistakes”, meaning that it is 500 years, each!

Tag line: The life of a fox is a full and complete life.

Case nr 2 from Mumonkan

Photo credit: kitsune

The Z Files

March 16, 2016

Resources